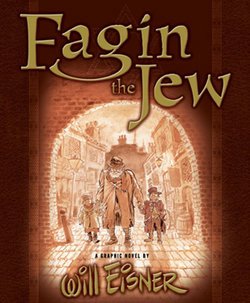

Fagin the Jew, by Will Eisner, Doubleday, 2003

Comics legend Will Eisner decided rather late in life that he would eschew superhero comic storytelling, and for this he is generally credited with “creating the graphic novel.” This encomium is perhaps a bit cultural-centric, as the long-form illustrated novel (and not merely the illustrated classics versions of “real” books) has a deep history in Europe and early twentieth century America. Lynd Ward in the 1930s in America produced several woodcut novels, while in 1926 the Belgian artist Frans Masereel published Passionate Journey, likewise a novel in woodcuts.

What Eisner is rightly credited for is bringing to the American comics medium a seriousness and a conscience in social biography. European and Asian artists have long recognized the form’s inherent strengths and were not culturally obligated to tell muscle-bound fairy tales for tots, the primary image one associates with the term “comic book.” For this we have to thank him. Without Eisner it is remarkably likely we’d have had little chance of seeing the work of Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and too many to name.

With the publication in 1978 of A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories, Eisner turned his focus to a series of interlinked short stories about tenement life in an immigrant, mostly Jewish, neighborhood. Definitely not something for the tights and tits crowd. He followed this up with more tenement stories such as Dropsie Avenue and The Building, and in 1991 To the Heart of the Storm, a tale about his joining the Army during World War Two.

The events of the war had profound consequences on Eisner’s personality and work. During the forties he had been writing and illustrating The Spirit, a hardboiled detective/superhero comic. The Spirit had a sidekick, a black boy by the name of Ebony White. His exposure to black soldiers in the war made him view his racist stereotype character with some alarm and he became more sympathetic to the character and softened much of the humor that Ebony was the butt of, the standard physical feature humor and poor grammar jokes.

Eisner has for a long time tried to weasel away from the evidence of this early work, claiming that that kind of humor was the dominant kind in the forties. This claim is true up to a point. There was a great deal of comic presentation of African-Americans for their humor value as poorly educated near savages interested only in food or sex. However, for an author and illustrator living in New York and growing up in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance, that’s a piss poor justification. For Eisner to be unaware of Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, James Van Der Zee, and (most tellingly) cartoonist and painter Romare Bearden is either ridiculously insulated or deliberately evasive.

Eisner continued, even in the last years of his life, to make the case that his racist caricature of Ebony was a “good stereotype” because he didn’t have cruel intentions. In the foreword to his 2

003 take on Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Fagin the Jew, he writes: “Ebony spoke with the classic ‘Negro’ dialect and delivered a gentle humor that gave warmth to balance the coldness of crime stories.” Ebony is pictured here for you the reader to judge. Eisner also makes a claim I’d consider a bit spurious, that there are “good stereotypes” and “bad stereotypes” and that “intention was the key. Since stereotype is an essential tool in the language of graphic storytelling.” (emphasis mine, and color me skeptical)

003 take on Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Fagin the Jew, he writes: “Ebony spoke with the classic ‘Negro’ dialect and delivered a gentle humor that gave warmth to balance the coldness of crime stories.” Ebony is pictured here for you the reader to judge. Eisner also makes a claim I’d consider a bit spurious, that there are “good stereotypes” and “bad stereotypes” and that “intention was the key. Since stereotype is an essential tool in the language of graphic storytelling.” (emphasis mine, and color me skeptical)Personally, while I can respect Eisner’s (later) intentions and can credit him with bringing to comics a gravity of subject matter (his last work was, after all, The Plot, a lengthy history of the production, dissemination, and eventual exposure as a fraud of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion), I have never liked Eisner as an author and only rarely as an illustrator. Some of the detailed renderings in his pictures is truly inspired and beautiful; the sepia-wash style his work has gives it an odd semblance to earlier woodcut novels; and his compactness in exposition is, panel for panel, among the best.

But his style never grew up with his content, his illustrations are filled with wide gaping mouths, bulging eyes, and waving arms. An Eisner book without fingers pointed at the sky in declamation is no true Eisner book. In Fagin (as in The Plot), Eisner’s rage at anti-Semitism expresses itself in vicious caricatures of everyone not a Jew. The cook at Oliver’s workhouse has vampirically pointed teeth; a Jewish Englishman who converted to Christianity is likewise ghoulish; while Bill Sikes is a gorilla and his doomed moll Nancy is a bucktoothed, big nosed dolt. The only character who doesn’t come in for any mistreatment is Fagin himself, who Eisner dolls up as a cuddly Santa Claus with big beard and belly, who only wants to help the street urchins he kidnaps and teaches in the way of theft.

Fagin is shown on the cover, a bedraggled old man with faint sleepy smile as he walks down the street gingerly holding the hands of two small tykes. Inside he is regularly shown as bestowing all kinds of kindnesses on the children, protecting them from Sikes’ rages, just a poor, misunderstood old man caught up in something bigger than himself. All of which is straight balderdash feel-good revisionism of the story. While Dickens may have unnecessarily constantly referred to Fagin as “the Jew,” there is nothing in Dickens’ Fagin that was particularly evil as a result of this element to his character. There was likewise nothing to suggest that Fagin was some kind of dear-hearted papa save for his verbal tic of calling everyone “my dear.”

Throughout the book there is more than just a few moments as well where Eisner just simply gets the Oliver Twist story wrong, such as when Sikes kills his faithful dog with a kick to the head after bashing in Nancy’s head with a chair. The story is at its best in Fagin’s early years and in the parts not concerning Oliver at all.

Eisner then makes in his afterword the remarkable argument that what are commonly considered “typical Jewish features” (big hooked noses, dark complexions, sharp features, the odor of Christian babies’ blood on their breath) are in fact Sephardic features “the result of their four-hundred-year sojourn among the Latin and Mediterranean peoples” and don’t apply in any way to Fagin. Oh no, Fagin, Eisner informs us (he did write the backstory after all and is entitled to this version) is in fact an Ashkenazic Jew, meaning he “had features that had come to resemble the German physiognomy.”

In one fell swoop, Eisner gets to have his cake and eat it too. These vicious anti-Semitic portraits are awful and immoral and besides, they are based on different Jews anyway. My Jewish criminal isn’t swarthy at all. He’s a jolly semi-Aryan. It is as if Eisner himself has come to subconsciously respond precisely the way those anti-Semitic illustrators wanted: with repulsion and sublimated self-hatred. This is unfortunate, a little bit sad, and cheapens the quality of the work. Both Eisner's foreword and afterword demonstrate neatly the adage that an artist shouldn't bother to explain his work, he should let it stand or fall on its own.

Because for all its schmaltz, its stereotypes, and its exclamations, Fagin the Jew remains an enjoyable read. It is educational without being dull or pedantic (I knew little about Jewish immigration to England prior to this and know considerably more now); it is entertaining without feeling light and forgettable; and it is clearly a case where the author’s love of his own creation has infused the work with a kind of magically contagious affection. Most importantly of all, however, is that it does what Eisner started out to do: it has broadened the possibilities of what we can expect from the graphic novel.

No comments:

Post a Comment