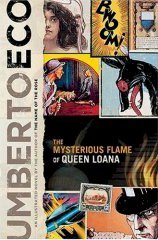

The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, by Umberto Eco, tr. by Geoffrey Brock, Read by George Guidall, Recorded Books, LLC 2005

The subtitle of Umberto Eco’s newest offering is “An Illustrated Novel” which suggests that it will rely quite a bit on pictures and will likely not translate well to the audiobook format. Having perused the actual print copy of the book, I can safely report that even though the various graphics — comic book clippings, bits of posters, and even a small illustrated series marking the book’s climax — accessorize the book’s story nicely (especially the Flash Gordon based ending), they are not ultimately essential. At least not for us.

For the book’s amnesiac narrator, however, these pictures are essential, they are the clues to who he is, they are, paradoxically, the frame that hangs around the missing portrait of his own existence. Through various pop cultural icons, our hero, Yambo tries to reconstruct not only his own life, but all his own secrets, now lost, even to himself.

Those familiar with Eco’s critical writing will recognize the tropes and the critical touchstones. Sherlock Holmes, Captain Nemo, Kafka, American superheroes. If you’ve been reading recent essays by Eco, you will note his current obsession/fixation with his childhood during Italy’s fascist period. It is part of a nationwide coming to terms with World War Two and Italy’s more barbaric behaviors, much of which had been swept culturally under the rug until Roberto Begnigni ripped that bandage off with his film Life is Beautiful. Prior to that film it was apparently in rather bad taste in Italy to even act as though such things had taken place.

The book’s opening pages are a bit confusing when listened to, consisting of snippets of literature run through disconnected dialogue. The literary passages, italicized on the page, are read in the same tone as the rest, only the most recognizable ones standing out to give you a notion of what’s going on. When “April is the cruelest month” trickles through his consciousness, it is a jarring obviousness. This trait becomes less pronounced as the book progresses, as his memory begins to fill in more Yambo’s the gaps, as his new experiences become more prominent in his consciousness.

While much of this book is truly enjoyable in the best of all possible ways, the lists that Eco piles up, all the encyclopedias the character of Yambo has created wear one down a bit going on for over one page. Likewise the depth of interest in name dropping odd Italian comics from the 1930s. But there are a number of charming facets, like when he tries to discover whether or not he had an affair with his assistant, whether he once wanted to, whether he tried and failed. The tentative tip-toeing he does around everyone regarding this is ticklishly delicate. Then there are almost childlike elements, such as when Yambo discovers some new thing, some obvious thing, and he tells us, “Tears are salty” and “You can’t look at the sun.”

Elsewhere, while reminiscing on comics from his youth, Eco and Yambo provide us with this deep consideration:

Arf arf bang crack blam buzz cai spot ciaf ciaf clamp splash crackle crackle crunch deleng gosh grunt honk honk cai meow mumble pant plot pwutt roaaar dring rumble blomp sbam buizz schranchete slam puff puff slurp smack sob gulp sprank blomp squit swoom bum thump plack clang tomp smash trac uaagh vroom giddap yuk spliff augh zing slap zoom zzzzzz sniff…

And that was as fun to reread as it was to hear. One can see Eco giggling a little as he types out that passage.

In tracking down all these mysteries, the book is filled with red herrings, false starts, snippets that might lead to something, might be important. It’s a mystery in which the mystery is who is the man who is telling the story and we work at it with him, watching him learn it.

The book’s third part, when he returns to Solara to his family home in the country deals with Yambo’s childhood, seems to lose the thread of finding out who he is in a greater sense and focuses on his coming of age story, as though this were the beginning and end of becoming who you are. This is not a fault of the novel, but a kind of natural outgrowth of the kind of story being told, of the kind of narrator we are presented with. Knowing nothing, who wouldn’t fixate on finding out about the time of their life when they most flowered? As he winds the narrative down to catching up in present time, Yambo begins to spiral into various philosophical Cartesian scenarios of brains in jars and mind control.

This is a decent return to form for Eco, who hit a bit of a weak patch with The Island of the Day Before and Baudolino, both enjoyable, but as is always the case, eclipsed by one blazing meteor right out the gate, The Name of the Rose. One is always hoping for a repeat performance of that original miracle. Loana isn’t that novel, but any novel by Eco is better than many and many a book taking up shelf space these days.

There was, however, something a bit off in this novel, something that felt tonally different from previous novels of Eco, a slight shift as though the book were written by an accomplished, though more serious, Eco impersonator. The blame for this I will lay at the feet of the translator, Jeffery Brock. Nearly every single previous volume of Eco’s work to appear in English has been translated by William Weaver and it is his Eco that has become my touchstone.

George Guidall, about whom much has been said in these parts, turns in a performance perfectly suited to his older, crustier voice. There are times I wished he’d apply himself more toward character inflections, but this is one instance, a man’s memories and perceptions of his memories (or lack thereof), in which such a singular perspective is a real benefit.

No comments:

Post a Comment