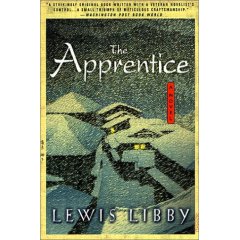

The Apprentice, Lewis Libby, Thomas Dunne Books, 2001

When I first told my wife I would be reviewing I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby’s first novel, The Apprentice, a turn of the century thriller set in Imperial Japan, she cocked her eyebrow archly and said, “Reviewing it? Or savaging it?” The impression I got, and I am not mistaken, was that my wife couldn’t believe that I am capable of an impartial criticism. That my hatred of the Bush Administration and everything connected to it was so blindingly white-hot that I’d lose sight of my critical ethics and rip the novel for the sake of merely ripping a Bush henchman.

I will admit that in my past such things wouldn’t have been beyond me. The temperament that dominated my twenties was an almost desperate need to revenge myself on someone, anyone, everyone for all manner of evils in the world, those felt by me particularly as well as those suffered by others, by humanity in general. Had I lived decades earlier I would have counted myself among the angry young men of literature, fist raised against hypocrisy, cant, and the banality of comfortable living — though really that would have only been a mask for my simply angry nature.

At any rate, I’ve come a long way toward being a more fair-minded person. Much remains to be done in that direction still, but here, on this site, I promise you that I won’t trash any work of art no matter how low on the talent scale, no, not even Mein Kampf, merely for the sake of scoring cheap political points. Should I savage a novel whose author’s political, social, psychological, or religious viewpoint I disagree with I don’t do it solely because of the authors’ orientation. That may inform my criticism, as when supposed Christians delight in the suffering of others in complete apostasy to their creed and stuff their novels with this rich, heady, and (to some) enjoyable suffering. But it’s not because I don’t believe in God that I whet my razor to slice these writers.

So it’s not because every member of the current Administration— yes, every single person — is a wretched, pernicious, and vilely disgusting biped-shaped toilet offering better stranded on some godforsaken Lord-of-the-Flies island that I say former Chief-of-Staff and National Security Advisor to the Vice President Lewis Libby’s novel is bad.

It’s because the book is bad, because the writing is bad, because the plotting is bad. Because after spending twenty years writing this dud, Libby has produced a vague, poorly worded novel tarted up with sex and then some murders — and those just so we know his motivation is pure.

How bad is it? Well, there are attempts at repetitious phrasings in sentences for poetic effect, such as this bland thing: “As he wrote, his head followed the character and he formed with his lips the words he wrote or wrote the words he formed.” Someone, anyone, explain the necessity, grammatically or artistically, for adding in that final clause. Then there is the overwhelming stupidity of the characters who fail to grasp what should be obvious even to peasants unfamiliar with the thriller genre. As night is falling, a group of four “wayfarers” arrive at an inn, as it happens just as a blizzard is coming up. Shortly after their arrival, another man enters the inn, looks around at the huddled guests, sees someone there, and then rushes out into the blizzard. He is chased by a hunter and the inn’s apprentice, some things happen out in the snow which I won't reveal, and when the apprentice returns, this conversation drags on interminably:

“Does a normal man travel on a night like this, reach an inn on the point of collapse, and then turn right around and run back out?”

…

“He was a thief. When he saw so many people, he became afraid and he ran away.”

…

“And why was he afraid of us? None of us knew him, and we wouldn’t be inspecting whatever he carried.”

…

“He wasn’t afraid of us…He was afraid of one of us….If he came to an inn he must have expected people, so we shouldn’t have frightened him. But when he ran out he was afraid…, afraid of one of us.”

I’ve cut out most of the argument which stretches onto three whole pages for these characters inexplicably to take so long to reach this obvious point, even if they have been at the sake. And there’s repeated instances like this, bad writing where people ask fantastically dumb questions as though Libby felt the need not just to beat you over the head with his plot point, but to fairly pummel you senseless, rather than just allude to things.

Then there is the snow. What Lawrence of Arabia’s tedious marches through the desert are to that film, long flights through the formless snow are to The Apprentice. There are no less than four long scenes in the snow, only the shorter two are of any particular dramatic note, the other, longer, much longer, two are faintly suggestive of possible drama. Maybe. “Someone’s following you” a monk tells the apprentice, but we see no one for pages and pages. Yawn.

Or consider this passage near the book’s conclusion where Libby is clearly going for poetic, philosophical effect:

On the morning of the final day the youth crossed along a north-facing slope where patches of snow remained. In them the hollows of men’s footsteps, long buried in the drifts of winter, could once again be seen. These footsteps began where the snow began in places where shadows often lay, and they ran until the sunlight where the snow was no more, and so they seemed to mark journeys of no distance at all that began without import and ended the same and held no meaning whatsoever save what meaning lay in their own passage. And it could happen that a wayfarer, crossing there, could come across these traces of his own way and know them not, or knowing them, have long forgotten what caused them to be; or it could be that he and the ghost of he that traced the empty hollows still might follow and precede and follow one another and look upon the same scene and see two things different altogether, and feel two things altogether different about what they saw.

Holy bleeding Jesus what a pile of dreck and dross, the kind of fourth-rate mimicry of third-rate imitators of second-rate passages from the lesser short stories of a college sophomore Faulkner fan. And the whole book has that kind of empty phrasings that just drone on and on and make you feel sleepy time always. The book is only some thirty pages over 200 and I found myself struggling and slogging through it for more than a solid week, making fists and forcing myself onward, ever onward. I made coffee thinking it was me, but even with half a pot stewing in my veins, I just kept drifting. It’s not that Libby never gets off a decent turn of phrase or a poetic image or a fine insight, it’s just that there are only five of these altogether, so you get one every forty-six pages.

The book is bad. Fine. That’s a given. I’ll leave it to others to harp on the salacious parts of the book, which are rather small, innocuous, and taken out of context give you a depressingly misleading intimation of what Libby’s book is about.

But part of what I want to do, instead of merely turning on the buzzsaw to some fairly atrocious writing, is to examine what I consider “political” reviewing.

Upon opening to the first actual page of the book, we find our bevy of blurbs. There are actually two full-ish pages of praise and three marquee blurbs on the cover. The very first thing to tip you off to what might be called a “political review” is the overwhelming provenance of the blurb sources. We note firstly, The New York Post, which is merely the print version of Fox News which tells you all you need to know. It is also written by John Podhoretz, a man so clueless about art he makes Michael Medved’s stool samples look like H.L. Mencken.

Says he of this snoozer: “more real and more vivid than the world you’re living in now.” No, really. He wrote that. Whatever high quality drugs you can score being a white legacy hire at all the name brand right wing rags, get me some of that. I too would like to read the telephone book and achieve a sense of rapture. Just look at this fool (photo included NSFS [not safe for stomachs]).

The second blurb is from Cynthia Grenier at The Washington Times, the uber-right-wing, Reverend-Moon-owned, money-losing fishwrapper where all the cranks on sabbatical from conservative think tanks find an open door, where we also find that “Mr. Libby makes the reader experience every scene with an intense vividness…in which everything seems real….” Again, with the “vivid.” You’d almost suspect the right wing had blast-faxed talking points for every possible occasion, but that’s just crazy talk. It’s fantastic, just unimaginably so, when an author, writing a book, using actual words, including dialogue, character descriptions, and settings, manages to make everything seem real. You’d almost think that was the whole damn point.

To this illustrious idiot role call, we can add two more names, Howard Norman, a real honest-to-god author of some critical note, and Ann Hulbert, one time editor at even-the-liberal-The New Republic (which also praised the racist piece of filth The Bell Curve under Andrew Sullivan’s tenure).

Then we jump right back to conservative hackery with The Weekly Standard, a magazine owned by, surprise, surprise, Rupert Murdoch, owner of The New York Post, which employs, on occasion, John Podhoretz and Cynthia Grenier. The Weekly Standard is edited by frequent Fox News commentator, William Kristol, who just happens to be a member of the Project for the New American Century, a wacky collection of neo-conservatives who also, coincidentally, include Lewis Libby on their roles. Oh yeah, and Norman Podhoretz, whose last name seems damn familiar, no?

This is all getting very cozy, ain’t it?

A newspaper of no note whatsoever (Advocate Weekly) chimes in to call the book “Reminiscent of Rembrandt,” in what can only be called the kind of hyperbole that makes Podhoretz’s earlier commentary seem like the reasonable observation of someone without extensive brain damage.

As for the cover blurbs one is by Washington Post Book World, and from what I’ve read of Post editorials generally, they don’t seem to be in the habit of bad-mouthing high name conservatives — it would get the authors off all the good party lists apparently. The New York Times Book Review is harder to pin down exactly. The Boston Globe makes similar points as all the conservative hacks made above, “atmosphere so convincing” which is the very least you’d expect from a book. But positive things being said about a conservative’s novel makes you want to cry out in the streets, “What good are you, damn liberal media!!??!!”

At any rate, I’m not so much a spring chicken that I find it hard to believe that people’s friends might write nice things about them or that right wing rags will come out in support of right wing vanity projects. Nor is it possible to imagine that there may actually be people out there who really do enjoy this novel, enjoy it wholly and entirely for it itself and not out of some brand loyalty or need to kiss ass. I just can’t imagine what else they might like. Stamp collecting? Hand-painting wood grain onto two by fours? Tweezing every hair on their body? It takes all kinds.

No comments:

Post a Comment