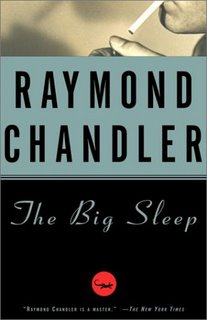

The Big Sleep, by Raymond Chandler, Read by Elliot Gould, New Milennium Books, 2002

Even if you hadn’t seen the scrumptious film version of Raymond Chandler’s first novel, The Big Sleep, it would be practically impossible not to view Humphrey Bogart in your mind’s eye. While the roles and his range were certainly wider than gumshoes, there is a sort of world-weary rumpled quality to Bogart (nowhere so well shown as Casablanca, naturally) that seems emblematic of the detectives of the forties and thirties.

Most likely this is a result of how closely Hollywood worked with the writers of these detective novels, Chandler having worked on the screenplay for the adaptation of James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity as well as The Blue Dahlia and the Alfred Hitchcock adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train. Sit and watch The Big Sleep with the text open in front of you and marvel at whole sections of zinging dialogue lifted verbatim.

Chandler’s style is poetic, bemused, and stands up to the test of time when his contemporaries like Erle Stanley Gardner have a musty taste of hokey old fashioned pabulum. Even Chandler’s use of now-outdated slang still pops with a crisp liveliness. His trailblazing work on the unexpected simile has become a staple in detective fiction as has nearly every other aspect of his iconic Philip Marlowe. So influential is his style that his name has been adjectivized, putting him in league with Shakespeare, Kafka, and Nietzsche, not to mention rating a song by Robyn Hitchcock.

That style, as stated already, is heavy on the similes, such as “A few locks of dry white hair clung to his scalp, like wild flowers fighting for life on a bare rock” and “...using his strength the way an out of work chorus girl uses her last stockings” when he describes his client, or when illustrating a liquid, “bubbles rose in it like false hopes.” “The minutes went by on tiptoe, with their fingers to their lips,” he writes elsewhere. There is an element of the nearly absurd in these; they walk to the edge of silly at times (which is what has made them so ripe for parody), yet the greatest of them contains a pungent whiff of despair.

Perhaps the most commonly quoted line about Chandler’s style is that of Ross Macdonald which gives this review its title, “Raymond Chandler writes like a slumming angel.” There is in that quote a fair praise, though an angel would have no cause for the despondency that hums through the prose. Chandler’s world weary detective is more than merely an authorial stand-in, he is a mouthpiece for an entire weltanschauung.

The Big Sleep features one of the more tangled plots in detective fiction, at one point even Chandler said he couldn’t make heads or tails of what he’d written. There simply isn’t much sense in trying to summarize the plot suffice to say that it’s the kind of story that is likely to actually happen in life in the way one job succumbs to mission creep and ends up taking in all sorts of associated unpleasantries.

A simple job of tracking down a gambling debt blackmailer turns into exposing a dirty book racket, uncovering a murder (or two), tracking down a missing bootlegger, putting a dangerously deranged heiress away, and avoiding being rubbed out by a vicious hitman working for a casino operator.

Through it all, Marlowe keeps his trademark sense of humor intact and manages to stay as true as he can to his knightly code of conduct. It’s not that Marlowe is lily white pure, however, it’s just that he is remarkably faithful to his sense of ethics, something to which Chandler’s inspiration, Hammett’s Continental Operative, shows nowhere near the same kind of adherence. In fact, Chandler might have inaugurated a sense of decency into pulp fiction, a kind of virtue that many of his contemporaries were quite comfortable in letting lapse.

As for the reading, I thought Gould, who was absolutely dreadful, just wrong on so many levels in Altman’s The Long Goodbye, made a very creditable reader. The slow delivery helps with the very confusing storyline and multiple characters that pop up throughout. Sometimes he gets a little cute with his voice characterizations, but it’s a small flaw for all that’s good in his reading. Gould’s deadpan style is pitch perfect and he does a very, very excellent job of resisting the temptation to ape Bogart’s iconic performance in the lead role. It is significant to our conception these days of detective stories, Bogart’s performances in this and in The Maltese Falcon, playing that other name brand American detective, Sam Spade.

If there is any gripe to be had with Gould’s reading it is simply his accent. The Brooklyn inflections that are impossible to shake off are simply out of place in Los Angeles, even if it is a city of transplants. Thus the choice of Gould is probably in and of itself more a tip of the fedora toward Bogart’s birthplace of New York and his own side of the mouth delivery than to Gould’s peculiar detective performance.

New Millenium, possibly a recent acquisition by Recorded Books released this as single tracked CDs. Why the higher quality corporation didn’t simply track the recordings is a cheap mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment