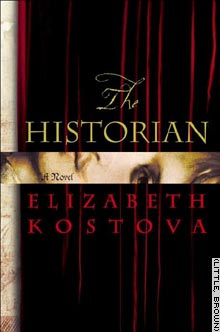

The Historian, by Elizabeth Kostova, Read by Justine Eyre and Paul Michael, Books on Tape, 2005

This novel is better than I had any anticipation of it being. I’d seen it among a friend’s luggage then later saw it at the library. Having just come off three weeks of nineteenth century novelists, I thought, Oh, something light would be a nice change. After all, I thought. Vampires. The book is about vampires. And not just any vampire, but the mack daddy himself, Dracula, the real Vlad the Impaler, who turns out to be the undead.

Light reading. Sure. Six hundred and fifty pages of vampires that is less concerned with torn pulsing arteries than with the minutiae of historical research. And much like Dracula, to which Kostova’ novel The Historian owes an incalculable debt (more so than many another vampire novel), the novel is constructed as a story within a story within a story.

One of the novel’s central conceits is how much of the story is told in the form of letters written by the young female narrator’s father. As this sum surpasses well over 300 pages in type, obvious plausibility considerations of scale arise, but only if you stop to think about it long enough. In the middle of the father Paul’s letters, he is handed a parcel of letters written by his mentor, Bartolomeo Rossi which are also substantially sized documents.

As their stories take them further and further into Eastern and Central Europe, the texts begin to shelter one inside the other inside the other like Russian nesting dolls. As the narrator reads the letters of her father, Paul tells of visiting a Bulgarian scholar who reads to him from a manuscript which includes in its history yet another person’s lengthy transcription of in fact one more person’s reminisces about Vlad Tepes. This kind of layered story is most definitely part of Kostova’s novel’s sensibility, and it’s rather an amusing in-joke.

What’s impressive about all this is how Kostova weaves three sizable narratives together, alternating time and place and narrative voice. We first are in Amsterdam of 1972 as our young narrator, a sixteen year old school girl, tells of discovering a mysterious volume in her diplomat father’s office and later of her journey to France. Part of what sends her out are the letters she is reading left to her by her father after he vanishes, telling of his travels and investigations into the Dracula legend in the 1950s Eastern Bloc. He is launched across the Soviet empire as well as through the byzantine mazes of Istanbul’s streets and libraries trying to discover what became of his missing mentor. Along the way as we try to find Rossi, we are told of his 1930s investigations into the Dracula legend in Romania.

On top of that, there are vast stores of erudition on fifteenth century monasteries, the cultural divide betwixt Romanians and Transylvanians, the Walechian court, medieval church politics, central European folk songs, Bulgarian religious rituals based around old pagan traditions, historian cataloging and research methodology, and the overlapping history of Central Europe with its shifting rulers of Ottomans, the Orthodox church and its tiny fiefdoms, and the Soviet Union. For, thinking about it as an historian, the undead would have lived through an impressive array of eras.

Consider this rather late passage:

The “Chronicle” of Zacharias is known through two manuscripts, Athos 1480 and R.VII.132; the latter is also referred to as the “Patriarchal Version.” Athos 1480, a quarto manuscript in a single semiunical hand, is house in the library at Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, where it was discovered in 1923…This original manuscript was probably housed in the Zographou library until at least 1814, since it is mentioned by title in a bibliography of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century manuscripts at Zographou dating from that year. It resurfaced in Bulgaria in 1923, when the Bulgarian historian Atanas Angelov discovered it hidden in the cover of an eighteenth-century folio treatise on the life of Saint George (Georgi 1364.21) in the library at Rila Monastery….The second and only other known copy or version of the Zacharias “Chronicle” — R.VII.132 or the “Patriarchal Version” — is housed at the library of the Oecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople and has been paleographically dated to the mid- or late sixteenth century.

Not your average vampire book, eh?

And that’s one of the funny things about reading this novel. At times, you have to remind yourself that this is a book about vampires. Not that Kostova won’t remind you at some point along the way herself, but that there is so much enjoyable writing throughout, so much fun detective work, that at times the supernatural element seems almost decidedly secondary.

Kostova knows well enough to keep the monsters off the stage as long as possible, merely make suggestive shadows lurk here and there on the periphery and affect a rather creepy atmosphere. After a point there are a hair too many overt murders that sap some of the menace, surprisingly, as they make the gathering darkness all too palpably concrete. Then there are a number of vampire staples that might turn up normally anyway. A bat flitters across a night sky. In the woods near a ruin, a wolf approaches the edge of the firelight. After sitting for some time near a railing cobby with webs, Helen Rossi, daughter of Paul’s mentor and mother to the unnamed young narrator, ends up with an enormous spider on her back. These stand-ins for the vampire are pleasantly unsettling without being accompanied by shrieking violins.

What propels each of the main characters, the young girl (whose name we never discover), her father Paul, and his mentor, Rossi, is the discovery of a mysterious old book among their own, a book with one printed page, that of a dragon with a banner reading “Drakulya” while the rest of the pages are blank. Throughout the novel we find that each character who has become obsessed with the legend of Vlad Tepes possesses a similar book that came to them under curious circumstances. Why and how these volumes keep turning up is one of the novel's mysteries an it's one of Kostova's rather clever conclusions in her own well-thought out realization of the character of Dracula. And there is throughout the book an enormous cast of characters, not merely just historical personages, but various researchers and students and librarians and bureaucrats and all of them are well-drawn, interesting, and fully fleshed.

We know, of course, from the very beginning, before the narrator even informs us, that when her father Paul speaks of a young beauty named Helen who he meets while trying to track down his missing mentor, that this will be the overtly absent mother of the young narrator. And, of course, since she is absent, we know there is a reason for that, and of course, as this is a horror novel, we know she is dead — or worse. Kostova manages to keep even that particularly familiar angle surprising. The author is at least a thorough-going plotter and she paces everything beautifully, setting up revelations with periodic sparks. All three story lines converge some hundred pages out from the novel’s end and from there the story picks up and aims squarely toward its conclusion.

The actual climax of the novel as our heroes close in on Dracula and his daytime resting place seems rather rushed, ending just all abruptly as if Kostova had opted just to skip overt dramatics, which feels a bit of a cheat, though she does make up for this lack of action with a final pages reversal that is as unsettling as it is quiet.

One reader, Justine Eyre, has a high, young girl’s voice which sounds appropriate enough when she reads scenes from her childhood, but when she says “I am fifty now” it jars somewhat. The two authors take turns reading, Paul Michael taking over for long stretches told in Paul’s letters. We first hear Eyre’s voice, then settle into a long tale that Michael unfolds in his warm, pleasant tenor, then cut immediately back to Eyre’s voice at its conclusion. The effect is nicely coordinated to jar you out of reverie and you return to the main story. Together, Eyre and Michael weave this multi-facted, multi-voiced book into a damn enjoyable listen that took me entirely and completely by surprise.

No comments:

Post a Comment