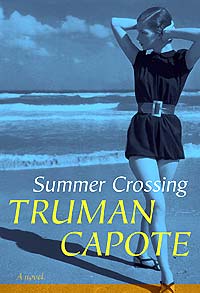

Summer Crossing, by Truman Capote, Read by Cassandra Campbell, Books on Tape, Inc., 2006

I’ve never read a novel by Truman Capote, though I’ve always meant to track down Breakfast at Tiffany’s since the movie is an undeniable pleasure. I think part of me resisted seeing the basis for the film simply because I wanted to believe that all the magic in the movie came straight out of Audrey Hepburn’s smile. But, with the success of the fascinating movie Capote, there is a renewal of interest in the author with books appearing about his black and white ball and the publication of the long-considered lost novel Summer Crossing.

Previous critics have spilled much ink about the book, about Capote’s genius in its formative years, about how posthumous novels so rarely satisfy, and about this as a failed work though with glimmers of future greatness. Again, having never read any of Capote’s work previously, I’m in no position to judge its merits vis a vis his oeuvre, though I can say that it was an entertaining if slight read.

The story is one of those types that are no longer written, a kind of hallmark of the forties and fifties (and to some degree the early sixties), a type of story of which Salinger wrote many, unselfconscious upper class tales involving people who summer in Paris and Cannes, carry little dachshunds with them, and have debutante coming out balls and heartbreaks. There is something almost touching in how innocently it’s all depicted through most of the book. A modern day novel about such type falls more to sneering at the wealthy, skewering their foibles with much less disguised affection.

The tale of a high-class girl Grady McNeil’s affair with a low-class man named Clyde Manzer is a bit of a cliched story only partly livened up by Clyde’s apparent Jewishness. I say apparent because though he makes mention of it, though Grady makes mention of it, it has the feel of being written by someone who didn’t actually know any Jews in person. Clyde might just as easily have been an Anabaptist or a crossword puzzler enthusiast or a weekend cyclist.

We rarely read “mixed relationship” stories anymore, a plot device completely out of fashion merely by its total commonplace quality, though one can easily see how more shocking such a thing might have been in the years this novella was written, 1942-43. In that respect, the book has curio qualities unrelated to its “genius in infancy” pedigree: it touches directly on ethnicity and class in the sort of sentimentally naïve way works from those years often did.

And lower-class Clyde most definitely is. Working as a parking lot attendant, he is as ambitiousless as his friends Mink, Bubble, and Gump, three stock types of mouth-breathing bar hoppers with dames and the occasional reefer habit. One supposes Capote saw such men riding subways and digging ditches somewhere, though perhaps to expect fully inhabited characters from a nineteen year old is asking a bit much.

In the other romantic corner, we have childhood friend Peter Bell, a flamboyant but decent young man from Grady’s own social circle, a sort of straight stand-in for the author himself. The pair have been just-friends for ages, and it is only with the discovery that Grady is in love with someone else that Peter realizes that he loves her himself.

What’s pleasurable about Summer Crossing, apart from its quaintly dated handling of subject matter, is that Capote had an ear for rather fine prose and even where it tends toward melodrama and the purplish quality so indicative of youth there reads the occasional gleam of beauty. In describing Grady and her mother’s relationship, we find this incident:

Once, but this had been a great many years ago and when Grady was still a tomboy with chopped hair and scaly knees, she had not been able to control them, her hands, and on that occasion, which of course was during that period which is the most nervously trying of a woman’s life, she had, provoked by Grady’s inconsiderate aloofness, slapped her daughter fiercely. Whenever she’d known afterwards similar impulses she steadied her hands on some solid surface, for, at the time of her previous unrestraint, Grady, whose green estimating eyes were like scraps of sea, had stared her down, had stared through her and turned a searchlight on the spoiled mirror of her vanities: because she was a limited woman, it was her first experience with a will-power harder than her own.

Later, in the novel’s final scenes, in despair Grady thinks of her own death: “All this would go on, these waves, these sea-roses shedding sun-dried petals on the sand; if I die, all this will go on, and she resented that it should.”

There’s some fine poetry for a 19 year old, no matter who he would or would not go on to become.

Reader Cassandra Campbell does a fine job reading in a breathy kind of way, though she’s more limited than many female readers in her male voices. Where Grady is her lightest trip through the story, all the men, even whimsical Peter Bell just plod thickly.

1 comment:

Hi there i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anywhere,

when i read this article i thought i could also make comment due to this good piece of writing.

Also visit my web blog :: chiarooscuros

Post a Comment