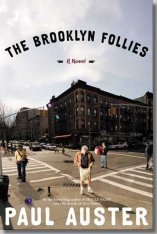

The Brooklyn Follies, by Paul Auster, Read by The Author, HarperCollinsPublishers, 2006

There are certain authors upon whom I feast. Once I discover them I tend to devour their entire catalog straight through, and usually, anal-retentively, I attempt to do so in chronological order so as to observe the author grow (Henry Miller and Knut Hamsun are two such examples).

There are, on the other hand, authors I choose to savor. Authors whose works I tend to dole out to myself with lengthy pauses between readings, stretching out and prolonging my experience with their writings or holding their novels in reserve as palliatives for the soul (A.S. Byatt and Tom Robbins come to mind respectively).

Neither category is better than the other, and were I to rank my favorite authors I’m sure the list would break fairly evenly between the two types. And each category, even the second, can bear repeat returns to the well. Hamsun’s Mysteries gets as many strolls down the hit parade as Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume.

Paul Auster is, for me, an author of the second category. Between my first discovery of his work with the stunning The New York Trilogy and the second book of his I read, Hand to Mouth, there elapsed four years. Between Hand to Mouth and Timbuktu six. Each book gripped me immediately, each book held me for the entire duration without slackening, each book was remarkably different from the other, and each book was memorable in a way few modern authors ever are.

It took me another three years to catch Auster’s latest, The Brooklyn Follies, and what differs here is that I actually anticipated this novel when I heard of its impending release. What’s also different is that Auster’s usual tone of somewhat intellectualized despair is leavened in a tale that ultimately is about redemption and how you make it for yourself. Exactly how this ties in to the novel’s final page occurrence is still unclear to me. I haven’t quite decided what the off screen (or page) invocation of the events of the morning of September 11th in the closing sentences of the book are supposed to mean to the novel — or to the author — but for now I’m satisfied with its inclusion. I wasn’t at first. They are not dropped in for sentimental effect, the inclusion doesn’t feel forced or shoehorned, and the novel stops so early that morning that the events have no bearing on the story itself.

It’s a puzzling inclusion, but puzzling in a good way, though not one to make you overly reflective. It’s of a piece with the rest of Auster’s work in that willfully blind cruelty can occur without the slightest of warnings, yet it unsettles the novel in a lingering way that is handled emotionally right. It is as if Auster were saying, there were these things in our life that we all thought were so entirely huge and important and in one respect they are, but in another they are not.

At any rate, not to make too much of what is only perhaps twenty to thirty words out of a 320-page novel, the rest of the book features the curious happenings in the life of our not quite hero, not quite anti-hero, common every day schlub, Nathan Glass. Auster arrests us with the book’s opening lines, “I was looking for a quiet place to die. Someone recommended Brooklyn” yet Glass never begs for the reader’s indulgence or sympathy. He himself even declaims his role as the book’s hero and instead attempts to pass off the title to his nephew, Tom Wood, the once promising grad student of literature who now works at a used book store.

His cancer in remission, Nathan actually has gone back to Brooklyn to die all but not in the sense that he believes it is imminent, rather as a kind of retirement away from all the cares of life. He has decided Brooklyn and no further will he go. There, in order to fill his time while waiting for that to happen, he decides to write a book called The Book of Human Folly in which he catalogs all the mishaps, gaffes, and slapstick idiocy of his whole life. When this fails to inspire completely, he includes those of his friends, things he’s seen and heard happen, and the errors of history.

The Brooklyn Follies, then is his telling of the events surrounding this work, and it’s kind of the most promising outtakes from said Folly. Through Tom, Nathan is reconnected to his estranged family, first his niece (through her curious daughter, a 9-year old who shows up on his doorstep refusing to speak for three whole days), then his own daughter. He also becomes friends with Harry Brightman, one time convict, now proprietor of the bookstore where Tom works, and becomes peripherally involved in Harry’s dreams of one last big score.

And here’s what’s so remarkable about Auster as an author. Having grown accustomed to rather extraordinary stories and their extraordinary characters, he springs on us an engaging tale about characters profoundly commonplace. And then he manages to turn the commonality of their existences into the stuff of heroism and resonating importance. Tom’s fall from promise is completely natural, his retreat into mind-numbing taxicab driving is a logical extension of events, his holding pattern at the bookstore a buried sign of life, and his late in the novel flowering comes off as a moment of personal strength and dignity.

And even better, what is the most dramatic act of the novel? Nathan challenges his niece’s non-confrontational yet oppressive husband and rescues her away from the passive-aggressive creep. Or perhaps it is Nathan’s nasty phone conversation with Harry’s con-artist ex-lover. Or maybe it’s a novel in which the climax is hard to pin down because there are so many normal stories going on which unfold as naturally as tulips that you’re past the actual moment of truth before you even realize it.

The stories Auster tells in The Brooklyn Follies are the little ones, the little lies we tell ourselves as self-esteem maintenance, family disappointment, hopes and dreams that prove just a little too far out of reach, and crushes on waitresses and women seen in the street regularly — the last the kind of rapture from afar whose tradition in literature has sadly withered on the vine. The joy in reading Auster is at times how natural his tales seem, so obvious and right there in front of your face, the idea so blatant anyone else must have noticed it by now. But no. Auster finds one miracle hidden in plain view after another.

And what a revelation it is to hear an author who is actually capable of delivering a reading without tediousness. Auster has a rich and velvety voice that occasionally lapses into a precise pronunciation stiltedness that somehow never jars, but almost seems Nathan’s own deliberation. He reads in an even timbre, never attempting impersonation of his characters, yet there is never a moment’s doubt or hesitation who is on stage. It makes The Brooklyn Follies worth owning in print and in audio, both versions warranting return visits.

No comments:

Post a Comment