Mom’s Cancer, by Brian Fies, Abrams Image, 2006

From the first pages I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect. Sure, Fies’ work is an Eisner Award winner, a book form graphic novel born out of an anonymous, online comic strip the author wrote as a kind of self-therapy while dealing with his own mother’s cancer. That alone is quite a bit to recommend the work. But there was something about the simplicity of Fies’ lines that gave me pause. It’s a little cartoony with very little depth of image (a complex panels is the narrator sitting in a chair watching TV, drapes behind him over his shoulder), so I worried I’d be getting a Hallmark card journey through illness and health.

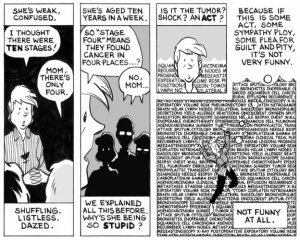

But there is something to Scott McCloud’s assertion made in Understanding Comics that the simpler the image the closer it approaches universality, which is to some degree an unintended point in Fies’ work. Written for himself to say all the things he couldn’t say to his family, to better understand all the things happening around him and to him, Fies’ work touched a chord all across the world. Word-of-mouth spread and increased the work’s popularity. The story, begun without intentional shape or structure, manages to jell nicely as a piece with the satisfying wholeness of a tale told without undue elaboration or dramatics.

To keep things simple, Fies limits the story almost entirely to the narrator and his two sisters, known throughout the work as Kid Sis and Nurse Sis, and the eponymous Mom. Doctors and nurses of various types float in and out through the story, as does a kind of spectral figure of the long-absent Dad. We watch in a kind of helpless fascination as Mom submits to treatment, first six weeks of radiation coupled with chemo (the radiation designed to get the metastasized node in her brain), then chemo alone to treat the cancer in her lungs. Technical aspects are not glossed over, but they are reduced to their most easily understood hearts, aided by Fies clarity of pen.

Mom’s Cancer is unsparing in its finger pointing. In one scene, in reply to Mom’s question: “Can you tell what caused it?” her doctor replies tartly: “In my experience, one of five things: smoking, smoking, smoking, smoking, or smoking.” In other places, as we watch a headshot of Mom as she undergoes treatment, losing hair and becoming more gaunt from panel to panel, we watch the stages of grief play themselves out including the confessional final shot. “But you know, I still want it,” Mom tells us here. “I’d smoke a pack now if I could.”

Unsurprisingly, the narrator’s observation after having nagged his mother to quit through the decades, “Somehow saying ‘I told you so’ turned out to be a lot less satisfying than I imagined” has the chest clenching ring of a true experience. For such a short volume with such simply drawn characters, Fies has managed to pour the essence of grief, the nub of experience into his pen and devastatingly out onto the page.

There were more than a few instances I found myself, hand to my throat as I read, blinking back tears. A panel late in the story, in the depth of her treatment, hairless, Mom turning to her daughter with a desperate panic in her eyes, tears streaming down her cheeks — she’s just found out after all these months that only five percent of patients in her condition live — made me set the book down until I felt I could continue. To look at it now, two weeks after I first read it, to see the stark beauty of Fies’ art in that one look is to catch just the faintest whisper of the despair of chronic illness of any kind.

It is also to see art, pure and simple.

The Sandwalk Adventures, by Jay Hosler, Active Synapse, 2003

Likewise in simplicity of style we find Hosler’s peculiar treatise on evolution as told by Charles Darwin himself to a follicle mite named Mara who lives in his left eyebrow.

You read that right.

Hosler writes a kind of simplified evolution without dumbing down the material (included is over twenty pages of endnotes breaking the work down at times panel by panel justifying and elaborating on the author’s choices), yet it retains a childlike whimsy and a weakness for cheap bodily humor and bad (really bad) puns. The latter two aspects are sure to provide the work with an appeal for its younger readers and would make it a delightful introduction to evolution at a very young age.

Which is not to say that Hosler’s work is simply a kid’s book. We are given a kind of thumbnail biography of Darwin’s life as two pieces as he explains his theory. The old Darwin, near death, as he strolls along a sandwalk near his home, tells of his discoveries to Mara and her brother Willy which naturally entails the story of his youth. As such, we are provided not only with an unconventional summation of evolution and natural selection, but an off kilter biography as well.

Along the way, Darwin breaks down the curious mythology of the mites, demonstrates that nature itself is just as worthy of reverence and fascination as the mythic tales of heroic demigod ancestores (if not more so), and explains evolution in such a fashion as to put it in a graspable form. This graspable form also has a few hidden digs in it, as the mites, in their ignorance, mouth sentiments one hears from coast to coast (but especially in Kansas) about the flaws in Darwin’s theory, flaws which more demonstrate their ignorance than any scientific lapse on Darwin’s part.

Much like Hosler’s previous science lesson disguised as a story, Clan Apis, the story of Nyuki the bee and her hive, told with an astonishing fund of information deceptively made simple, The Sandwalk Adventures is a high-spirited educational work that reads lightly, quickly, and best of all entertainingly. At the end of the work, through all the laughs, you suddenly realize — hey, I learned something in all that fun.

Which was Hosler’s plan all along.

Marvel 1602, by Neil Gaiman, Andy Kubert, and Richard Isanove, Marvel Comics, 2004

To an outsider, that is, a non-comics reader, there may seem little difference to the two major publishing houses, Marvel and DC. And to be fair, there are more things they hold in common than keep them separate. But all through my life, I’ve never cottoned to Marvel’s material.

Superheroes are, for the most part, one’s initial experience in comics, and most readers are turned off at the get-go. This is unfair, rather like rejecting television out of hand because of Life with Jim. Sure, the show is shit, sure there are far too many shitty shows just like it, but then there are gems all throughout.

Nevertheless, Marvel, the newer of the two publishing firms does differ from DC in part because the focus is so all encompassingly on the superhero genre with precious little else in their roster’s history. The tights, the silly costumes outside of that, the ridiculously suggestive and unnatural physiognomies, and the preponderance of exclamation mark leaden dialogue of the “Gee Whillikers! It’s smashin’ time!” variety are only half of the story. The other half is, unfortunately, just as bad.

So it was with quite a bit of surprise that I happened across the title Marvel 1602 the other day and noticed the author’s name on the cover.

Neil Gaiman is best known for his work with various DC titles, most prominently his long running, successful and award winning Sandman series. He has written so long for DC that one kind of thought of him as an in-stable talent, a loyal DC’er with the kind of freedom to do some small independent work. Not the kind of person to jump ship for the competition.

And not the kind of person to want to associate himself with a company with major characters bearing such ludicrously personality telegraphing names as Nick Fury, Doctor Strange, Captain America, Magneto, and most absurd of all, the villain, Doctor Victor von Doom. Is it any wonder adults dismiss graphic novels as kid stuff?

But the cover was intriguing. The 1602 alluded to in the title, based on the artwork, seemed to suggest Gaiman was working in an historical vein. Which is exactly what the man did. He took classic Marvel characters and transposed them upon seventeenth century Britain, tweaking them considerably.

I myself was relatively unfamiliar with a number of the major players, such Fury and Strange, who play competing and at times allied advisors to Queen Victoria, though the lesser roles were more known to me. The X-Men one can’t help to have some familiarity with these days with the glut of movie tie-ins, nor should Bruce Banner (the human guise of the Incredible Hulk) be entirely unknown, nor less Spiderman or The Fantastic Four.

Gaiman twists all of these associations, denying Banner and Spiderman’s alter ego, Peter Parker (here, amusingly Celted up to Peter Parquagh) their special powers, adding an Inquisitional touch to the persecution of the X-men mutants, and mixing all of this up in the waning of Elizabeth’s powers alongside the rise of the Scottish king James and the joining of the two kingdoms.

The story is delightfully suspenseful, entertaining even if you don’t know (or care to know) the whole Marvel mythology, and satisfyingly rich. Gaiman has a knack for creating comic book characters with depth, who have a kind of off-the-page life of concerns and worries that he can gingerly allude to so as to give you the entire story in a line of dialogue. Gaimain’s long-standing interest in mythology serves him well in this regard, as he distills down the archetypal aspects of the characters, tossing aside their modern day fanfare and fripperies, and translating them to a much earlier epoch in a well carried through form.

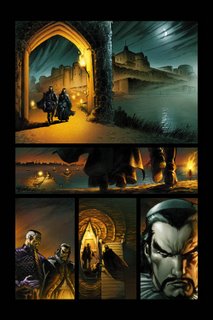

Kubert and Isanove provide a nicely textured page with illustrations both as heavy as a woodcut and as light as the most delicate tracery on an illuminated manuscript. Some of Isanove’s computer generated color has at times a moderately plastic feel, though thankfully this is rarely overt. The whole thing reads as divertingly as the old comics of yore Gaiman praises in his afterword, which is probably the biggest surprise to me of all.

No comments:

Post a Comment