The Brief History of the Dead, by Kevin Brockmeier, Read by Richard Poe, Recorded Books, LLC, 2006

Even though it is generally a rare thing for me to read adult novels of the supernatural (and an even rarer occurrence for me to like them), listening to audiobooks has significantly altered my typical reading habits. Books I wouldn’t waste the several days worth of consecutive sitting and concentrating on in print pass breezily by me in two days worth of listening at work. After doing a bunch of heavy lifting with Henry James and the like, sometimes kicking back with a penny dreadful is just the thing, too. It sort of washes the palate.

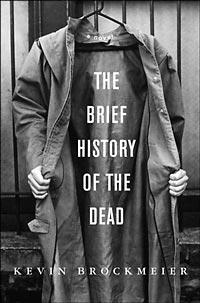

Now, it is entirely possible I might have actually read Kevin Brockmeier’s latest novel, The Brief History of the Dead, despite the ghost-story tinge, sucked in at first by the rather eye-catching cover, then by the actual idea of the book. It’s an interesting conceit. A rampant, vicious, and deadly plague, war, and the breakdown of the social order attending it are wiping out the planet’s population while three people become stranded at an outpost in Antarctica. The two men in this lonely last vestige of humanity set out in search of another larger polar expedition camp and aren’t heard from again, leaving Laura Byrd as quite possibly the last woman alive on Earth.

Meanwhile, the population of a kind of parallel Earth is growing. The recently dead keep pouring into this city landscape, filling it with their afterlives and it merely grows and grows and expands outward, no one ever reaching its farthest border. The recently dead all exist in a strange sort of afterlife, a place they call “The City,” and Brockmeier gives us this little fine instance of description:

Occasionally, one of the dead, someone who had just completed the crossing, would mistake The City for Heaven. It was a misunderstanding that never persisted for long. What kind of Heaven had the blasting sound of garbage trucks in the morning and chewing gum on the pavement and the smell of fish rotting by the river? What kind of hell, for that matter, had bakeries and dogwood trees and perfect blue days that made the hairs on the back of your neck stand on end?

What keeps these people in this median stage between life and the true afterlife (or non-existence) is the memories of those still living who remember them. When the last people on earth who remember you die, then you leave The City, vanishing into whatever comes after, if anything. The City’s ranks swelled rapidly in the last few months as plagues and wars and terrorist acts slaughter populations by the millions, by the billions. But, as more arrive in the City, mathematically, eventually, a point is reached where more must leave. Finally, all that remains of the planet of the living, and all that remains of The City comes down to one person, Laura Byrd, stranded in Antarctica with her memories.

There are curious elements that turn up in the afterlife. Thunder storms, flocks of birds, a giraffe whose spots float right off of it into the air. It begs the question of exactly how much memory will remain; why do elements of the city not in Laura’s memory or the deads’ memory remain in place? If this afterlife is hinged entirely on the existence of memory, would it not itself shrink considerably once it begins to be depopulated? Instead The City is a long time in shrinking, suggesting that sometimes landscapes linger in the mind longer even than people, the stage empty after the cast have left.

When The City appears to be all but uninhabited, we follow three characters, a nameless blind man, the publisher of a newspaper in The City, and a young woman. They travel The City looking for others when the blind man hears a gunshot going off regularly. Heeding its call, they make it to a part of The City called the Monument District where they are astonished to find over two hundred people. This eventually swells to a few thousands.

If that seems large, consider your own memory, think of the fullness of your recollection. You will be startled to find that it is populated by legions, most bit players who wandered into your consciousness only to never fully leave as though our brains were one large squatters’ residence, a cast of extras into the five or six digits.

Brockmeier writes the best kind of supernatural novel, the kind in which the elements aren’t fully explained. Yes, we learn that it is Laura’s memory that keeps The City alive at its end, but we are never told why the universe works like that, whereas certain practitioners would have to include some sort of explanation of the mechanism. Psychic echoes or vibratory memories or some such. Instead, things merely are, which frees up Brockmeier to make the focus of the story the intangible aspects of memory and allows him to give us an extended consideration of the nature of it. This is a ghost story for adults, without the actual booga-booga qualities.

One chapter starts off with the jolting, but necessary, “Dying had changed Mary Byrd.” Herein we learn of Mary and Phillip Byrd, Laura’s parents. We read of things Mary once loved about her husband, then came to not love so much (came rather toward distaste and loathing actually), then finds herself falling in love with all over again in the afterlife. “She caught herself sighing. In the sound, there was the echo of the one long sigh that had been the last few years of her life.”

Along with this afterlife love (for Mary and others) also appear strange moments of chronological lapses. In the afterlife, while Mary and Phillip (and others presumably) still lived, Mary’s mother, who died long after Laura came to know her, was reunited with her dead husband who was himself long dead before Laura’s birth. After a certain stage, he then disappears, leaving Mary’s mother to grieve her loss a second time.

There are all kinds of curious questions that slowly rise to the surface when we consider these questions of memory. Are the dead people themselves as they think of themselves, as they remember themselves, soul as a kind of personal memory? Or instead are they chunks of other people’s memories, souls as constructed in the memory of other people? Put more simply, because Laura always thinks of her coworkers Joyce and Puckett together as partners, as a set, is that why they always run into each other in The City? Because Laura has them circumscribed within each other’s lives? If Puckett were a closet panty-sniffer, would this aspect of his “soul” exist in The City or would it cease to be true because Laura was never aware of it?

Brockmeier doesn’t spend much time laying out every aspect of this curious afterlife, but it isn’t necessary. Instead, it is a sign of how an intelligent book with a novel premise can set the mind to wondering and wandering over its general propositions. (As a nice touch, certain egotistical people in The City think that they are there because for some reason they remember Laura, instead of the other way around and they’re irritated by this.)

The chapters take turns telling of Laura’s decision to leave her first Antarctic base in search of her coworkers and her general struggle to return to a world of safety (she remains mostly oblivious to what has transpired in her absence). Each narrative return to The City from Laura’s story tells a short almost self-contained tale that slightly advances our understanding of the community and what keeps them there. The tale of the sandwich board evangelist is a touching portrayal of a kind of commitment to an idea that may seem madness to most, but also has an almost admirable single-minded devotion to it.

Then there are casual little bits of the story that seem all too plausible and bitter laughs well up. In the real world, once reports come out that terrorists were trying to poison American cities’ water supplies, the Coke company hired ten thousand beautiful people to dine out at fancy restaurants across the nation and ask anyone they overhear ordering a glass of water: “Wouldn’t you feel safer drinking a Coke?” It is quite a bitter little joke when it becomes clear later that the virus was deliberately spread through the ubiquitous Coca-Cola.

The book’s closing chapters after Laura moves from the land of the living lose a kind of forward momentum and urgency, though when Brockmeier shifts back to The City, there is ironically a sharp clench of life. Desperation sets in with the residents as The City’s outer edges simply disappear. A bicyclist who reports on the nothing there describes trying to ride through it as like cycling up a sphere: he can feel himself moving, but he doesn’t go anywhere. Day by day, The City shrinks.

For a long time it had seemed to him that there were more people on the streets, more people in the park than ever before, but it was only now that he understood why. As the City became smaller, they were all being drawn toward the center. They were like pieces of bark and foam caught in a gigantic whirlpool. And at last he apprehended what was happening. When the walls came together and the bubble finally collapsed, this was where they would all end up. Right here, between these benches and rustling trees. It would happen in a matter of days or weeks. There would be no way for them to avoid it. They would gather together in the clearing around the monument, however many thousand of them there were, and they would stand there, shoulder to shoulder. They would listen to each other’s voices, and they would breathe each other’s breath, and they would wait for that power that would pull them, like a chain, into whatever came next. Into that distant world, where broken souls are wrenched out of their histories.

Reader Richard Poe turns in a stand-up performance here, never once giving in to the male temptation to try characterizing female parts, though his voice has slight intonations, drops in pitch, and other little tricks of the trade to keep us completely aware of the action. His rather authoritative voice gives plausibility even to theoretical concepts such as this.

No comments:

Post a Comment