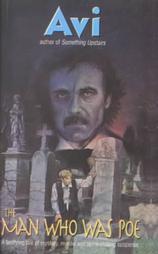

The Man Who Was Poe, by Avi, Read by George Guidall, Recorded Books, LLC, 1995

When you review anything different standards apply based on what is under the microscope. You wouldn’t apply the standards of what makes good classical ballet to a square dance competition, nor should a mindless action picture be judged by that which we apply to the existential ruminations of Ingmar Bergman. (What precisely constitutes a “good” anything is a discussion we’ll leave for another day.)

My first feeling on reading the description of Avi's The Man Who Was Poe was a kind of disappointment that the focus should rest so heavily on "the macabre tone of Poe's fiction" and "cold-blooded murder, brutal calculation, and historical intrigue." Then I checked myself and recalled that singularly named Avi was not writing a novel for adults, but for children, and if anything children are more fascinated by the morbid and the macabre than are adults.

A children’s book then ought not to be expected to live up to quite such an exacting standard as an adult’s. I kept trying to remind myself that in tempering my remarks while preparing notes on the book. But my original feeling of disappointment was no match for my growing sense of same in listening to the work. It is hard to know precisely, in regarding this work, how much is badly done by design and how much is badly done through accident.

I’m not really sure why the author actually included Poe in this novel at all. Perhaps he hated the author from having been made to read Poe in school or he hated Poe just because, but there seems little reason to drag the author into the story. The novel is focused on eleven year old Edmund who is trying to find his sister and his aunt. A few days previously, his aunt left the two alone in their room with strict instructions not to go out. She never returned. Hunger forced the two children to decide upon older Edmund to disobey long enough to run down to the nearest tavern for some food. When he returned, his sister, Sis, was gone. Edmund tries to locate her and is assisted, after some fashion, in this by Poe, whom he runs into in the street.

Intertwined in this then is the story of Poe’s doomed romantic engagement to minor poet Sarah Helen Whitman, an attachment sought after partly for companionship and partly for Whitman’s fortune, which would have allowed Poe to run his own magazine. While Poe’s last years were marked by erratic behavior, what Avi provides here is a dangerously deranged individual who’d not likely have lasted long on the mean streets of nineteenth century America. A man unlikely to be able to concentrate long enough to compose even such a short verse as “To Helen.”

Instead we meet a rude little bastard who insists on being called Auguste Dupin, prey to fainting spells and delirium tremens and showing a callousness toward Edmund that is almost supernatural in its selfishness. At the same time, Poe seems to be wracked with a hallucinatory madness. He sees ghosts in crypts, then at a tea party at the home of his hopeful intended, he seems unable to put ratiocination to good use, thinking all the guests are demons there to assault and torment him. This is neither the most probable explanation, nor one that lends itself to reason. Yet, when on the trail of the crime, his rationality is attended in high relief. Poe’s slipping and sliding into and out of madness is harnessed more as plot device than organic part of the character’s psyche, cropping up when Poe is not needed for plot advancement or when the arrival of said madness would provide dramatic complication. It feels rather opportunistically used and presents an utterly loathsome picture of the man that sits oddly inside the novel, never quite settling down comfortably nor provoking us with ironic discomfort.

This madness is taken so far that at one point Poe, having for quite some time passively refused to continue the search for Sis because he is using the events to write a new story and in his story it is better that she dies, actively holds Edmund back when he could save her. While Poe was quite disturbed in his life especially near the end, and while he held deeply romantic notions of art, such extreme behavior is a slander and a bit vicious. That viciousness is furthered by having the man tell Edmund at the novel’s conclusion that in his story, Edmund's sister would have had immortality while in this life she'd only have her short little human life. I've rarely seen anything quite so close to fictionally digging up a corpse only to spit in its face.

While Poe may have written a great number of characters who, in their fantasizing, find their greatest enjoyment while considering such things as "shipwreck and famine; of death or captivity among barbarian hordes," it is rather certainly likely that given the choice in real life they'd pick safe passage and feast over their absence. The idea that an author might himself be as morbidly pessimistic in his actions as his characters' fantasies is a calumny indeed. It is to think that Stephen King murders people regularly, that Raymond Chandler went around slugging guys and digging up the truth, that authors are indistinguishable from their works. It is a piece of juvenile foolishness.

And what makes it so irksome is how unnecessary it is. That it is Poe in this story and not someone else feels done merely for the sake of book sales. Just as easily could it have been an adult inspired by Poe’s writing or just an odd adult. Poe here feels like a device and a poorly used one at that. The author’s fundamental disrespect for his own character creation undermines the book at every step.

At any rate, much of Edmund’s story is well written with rising suspense and action. A real sense of menace pervades the book, as it truly would for an eleven year old suddenly abandoned and completely alone in the world with not one single friend to turn to. There is a very good reason why absent parent stories are so popular with children. It is, to wit, the existential crisis of their lives. Without my parents, who will take care of me, where will I get food, where will I sleep, how will I live, who will protect me?

These kinds of stories function as coming of age tales as the children generally either need to rescue their parents or manage to find a way to survive on their own. In our far more welfare-oriented society, such tales aren't nearly as popular as the prevalent coming of age type and tend to be dismissed by older readers, but remain widely sought by children as existential horror stories. Coming of age tales now, in a far more comfortable society, take place later in life and typically feature far fewer nightmares. The focus has shifted from the rather nuts and bolts of sheer existence to a kind of psychological existence. In place of who will feed me, we now have, who am I? The latter is indeed a pressing question, but one more likely to be asked by those who know from where their next meal is coming.

What’s finally left here is an uneven book, uneven even if judged by the lighter standards one might apply to a book aimed at younger readers. Edmund and Edgar, a study in contrasts in Shakespeare can equally be seen as a pair of opposites in Avi. With one, our story grips, it compels, it moves along with a kind of desperate energy; with the other, it is too scattershot to even fix our attention.

Reader George Guidall does his thing and does it beautifully. I’m almost at the point of leaving out altogether any comments regarding the man’s work. It would be noteworthy if he turned in a bum performance; even his steady perfection is no longer surprising.

No comments:

Post a Comment