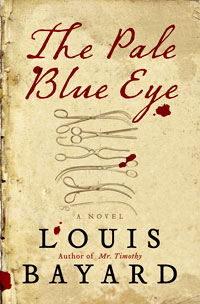

The Pale Blue Eye, by Louis Bayard, Read by Charles Leggett, BBC Audiobooks America, 2006

When most people think of Edgar Allan Poe what comes to mind is the gloomy tales of the macabre and the poem “The Raven.” Ask someone a little more versed in Poe and they’d be able to tell you he’s also credited with basically inventing the genre of science fiction as well as mystery. A Poe scholar could point to his abundant literary criticism, his philosophical dialogues, and his cosmological big bang theory that predates the so-called theory by nearly one hundred years.

Thus when choosing to paint a fictional portrait of the man Poe you have several different aspects from which to draw, though shamefully most authors zero in on the author’s alcoholism and debased final days (note I do not say “debauched”). Following up his debut novel, Mr. Timothy, the adult life of Tiny Tim from A Christmas Carol, Louis Bayard has chosen to focus on Poe the romantic and Poe the proponent of ratiocination — which may sound contradictory.

Told in first person as a narrative document, The Pale Blue Eye tells the story of August Landor, a retired detective nursing personal demons who is summoned up out of his retreat to investigate the death of a young cadet, Leo Fry, at West Point. It seems the young man was hanged, then his body disappeared from the morgue. When it was later found, he had had his heart cut out. While on the campus, Landor is accosted by a sallow youth who explains to him that whoever cut out Fry’s heart must have been a poet, the heart being such a potent symbol to men of letters.

Landor convinces West Point’s stuffy superintendent Thayer to allow him to semi-officially deputize Poe as his agent among the cadets, and what follows is a deepening relationship between the two men as they probe secrets high and low amid the Hudson River Valley’s military families. Their relationship is tested by Poe’s penchant for dramatization, for embroidering his own biography (such as telling other cadets he is related to Benedict Arnold or that years ago he killed someone), by both men’s fondness for drink, and by a second murder.

Bayard has done something rather clever here in enjambing both the popular mismatched-buddy cop story and the Poe-prototype detective and companion story (a ball Sir Arthur Conan Doyle took and ran with), but he’s made the relationship real, deepened the connection. When Landor begins to mistrust Poe (and for reasons all his own), he slaps the poet down hard, the scene a vicious verbal assault on Poe’s fabrications, on his little sister’s illegitimacy, and his actress mother’s profligacy, a scene of such unexpected brutality that I stopped what I was doing and gripped my desk, listening white knuckled. It’s a rare author who can make the violence of language palpable.

The first person memoirs of Landor are supplemented by Poe’s manuscript of his own inflated accounts of his investigation and both provide a nicely twisted example of unreliable narrators. A number of Poe’s most recognizable phrases are salted throughout, such as in a lengthy report he delivers to Landor, phrases such as “watch wrapped in cotton” and “Plutonian darkness.” Their chronicles detail their twin track investigation into the duo’s primary suspects Artemis Marquis and Randolph Ballinger, upper classmen and supposed Satanists. Falling in with the pair, Poe quickly forms an attachment to Artemis’ sister, Leah, who later demonstrates a tendency toward “the falling sickness” (epilepsy) and some queer quirks of her own. Both he and Landor note the Marquis mother’s habit for nervous hysteria edging toward mania and note it well.

All in all Bayard’s portrait of Poe is an interesting one. We see the gloomy tendencies that would dominate much of his most famous writings and poetry, but in a kind of showy adolescent form as in his insistence that the death of a beautiful woman forms the prime inspiration for poetry. At times I was reminded of the joke that the Bible never shows Jesus’ troubled adolescence, only the miracles and the patience. One typically only imagines Poe as an adult, the drunken widower with a penchant for morbidity and a fear of premature burial and fails to imagine the youth: eccentric, eager to please, desperate for the admiration and approval of certain other people while at the same time tipping toward over-familiarity and disrespect so common to that age.

Just as interesting is his characterization of Landor. His memoirs tends toward a kind of proto-hardboiled detective with phrasing such as these which wouldn’t have been out of place in Ellroy or Hammett: “The other fingers broke faster or maybe I just knew how much force was needed” as well as “And there I sat smiling, coatless and damp, asking myself, ‘Which of the people in this room just tried to kill me?’” At the same time, Landor's unburdening to Poe of his secrets is a heart-wrenching account of helplessness. If there is a likely flaw in his styling, it is that his tale involves far more sexually explicit material than would seem likely for a man dead before the turn of the century.

When halfway through the story Ballinger, our number one suspect is murdered, and Poe becomes the prime suspect for this murder and the previous one as well, the academy separates the two detectives. They continue to meet in secret and their relationship moves to a different plane here as the older man begins manipulating the young poet as the two move ever closer to the truth.

The book gallops with a modern thriller’s pacing in the last few chapters as we seek out our climax, though it’s a testament to Bayard’s skill in plotting that we feel uneasy and eager to move toward resolution long before the speed picks up. The book’s concluding chapters are a swift kick in the stomach as the frame you come to expect is shattered right before your very eyes. Bayard proves a masterful storyteller in undoing expectations while in some fashion living up to them engagingly.

Charles Leggett is another one of BBC Audiobooks America’s stable of talent not familiar to me. A Seattle stage actor who’s done some voice work for video games, he delivers this material with aplomb and never overdoes the southern connection in Poe’s voice, though his croaking delivery of Landor’s phrenology obsessed Indian friend Paw-Paw gave me the giggles unrelated to the character’s comic relief activity.

No comments:

Post a Comment