One of the great pleasures of my college years was the discovery of Evelyn Waugh. There are a great many authors and books from that time period that shine with a transcendent memory so lasting that to encounter the works in later years is to be just a little disappointed. Part of what made them so effecting was the immediacy and constancy of the feeling one has in one’s early twenties that your mind is a flower always bursting open. The right book in those years can alter your life in a way that is ever less common as you age.

One of the great pleasures of my college years was the discovery of Evelyn Waugh. There are a great many authors and books from that time period that shine with a transcendent memory so lasting that to encounter the works in later years is to be just a little disappointed. Part of what made them so effecting was the immediacy and constancy of the feeling one has in one’s early twenties that your mind is a flower always bursting open. The right book in those years can alter your life in a way that is ever less common as you age.What a joy to then pick up any of the Waugh books I first read in those gin-soaked years and to come away still zinging with the lushness of his prose, the acid bite of his observations, and the fearful yet comic iconoclastic brutality with which he demolished pieties small and large.

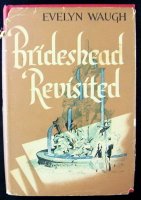

Brideshead Revisited, however, is unlike any of his other books, an aching, melancholic look back with tenderness at the very years just discussed and the fallout from them. Certainly the Waugh wit is evident, especially in scenes featuring the protagonist and his retiring, misanthropic father, yet, this is a haunted book, a shaded rumination on the past and all we lose. It contains within it also a serious argument on the sanctity of Catholic faith and the striving for grace and redemption.

Narrated as a look back by Charles Ryder, currently serving as an officer in the British army during the Second World War, the novel is subtitled as the Sacred and Profane Memories of Capt. Charles Ryder. It is the latter adjective that makes up the bulk of the book, focussing as it does on Ryder’s relationship with the aristocratic Flyte family, most specifically his alcohol marinated friendship with the younger son Sebastian and his later doomed affair with Sebastian’s sister Lady Julia Flyte. Other members of the family include the absent, estranged father, Lord Marchmain, the icy, demanding mother Lady Marchmain, and the youngest child, Cordelia, who ends up a nurse in the Spanish Civil War.

The reminisce of one’s college days has a lovely falling air, the kind of romantic prose poetry where it is always just nearly dusk, where one is always lying under the shade of trees, where one’s friends spout so much erudite nonsense, where one adopts poses and changes them as one changes one’s shirts. Waugh manages to catch that quality of late adolescence/early adulthood which is marked most by competing languor and freneticism; there is no reason to get excited about anything, until there is, then enthusiasm necessitates tearing off in a car for champagne and strawberries or other such important matters.

Charles and Sebastian’s friendship carries elements of homoeroticism to it, two taxi dancer types calling them “fairies” while the mistress of Sebastian’s father notes their nearly-grown-male love for each other. There are narrative tip-offs that this may be an actual physical relationship never quite discussed (Ryder alludes to this elusively with the phrase “our naughtiness was high on the list of grave sins”), though Waugh leaves it open to question (whether by design or censorship is difficult to pin down).

Early on Sebastian predicts to Charles that if he introduces the narrator to his family, they will steal him away from Sebastian. When Charles does meet the family, coming to stay with them for Christmas and at other points, it isn’t so much that the family spirits Charles away but that Sebastian starts to recoil from his friend as he draws back from his family. There is a hidden sorrow or pain in Sebastian’s personality, which spurs on his drinking and his later moodiness. Neither Ryder nor Waugh ever pierce the heart of this misery.

There is in Sebastian’s dipsomaniacal behavior the feeling of watching a car wreck in slow motion, one sees the impact long before it occurs, one sees the blood, the tears, the disaster. That Ryder develops a cheerless personality as a result of this, that it should so hover over his life, is completely natural and believable. This quiet despond is further deepened by the stumbling and ultimately futile relationship with Julia.

Having embarked on a career as an architectural painter and gotten married, having not contacted any member of the Flyte family for several years, Ryder happens to meet Julia, separated though not divorced from her husband, aboard a cruise ship. His wife and most of the other passengers laid low by seasickness during a lengthy storm, Ryder finds first company and then love on the open water with this old friend from his youth. The scene preceding their affair rings with a beauty and clarity I had not forgotten though more than ten years passed between the first time I read it and this time:

She rose and, though the roll and pitch of the ship seemed unabated, led me up to the boat-deck. She put her arm through mine and her hand into mine, in my great-coat pocket. The deck was dry and empty, swept only by the wind of the ship’s speed. As we made our haulting, laborious way forward, away from the flying smuts of the smoke-stack, we were alternately jostled together, then strained, nearly sundered, arms and fingers interlocked as I held the rail and Julia clung to me, thrust together again, drawn apart; then, in a plunge deeper than the rest, I found myself flung across her, pressing her against the rail, warding myself off her with the arms that held her prisoner on either side, and as the ship paused at the end of its drop as though gathering strength for the ascent, we stood thus embraced, in the open, cheek against cheek, her hair blowing across my eyes; the dark horizon of tumbling water, flashing now with gold, stood still above us, then came sweeping down till I was staring through Julia’s dark hair into a wide and golden sky, and she was thrown forward on my heart, held up by my hands on the rail, her face still pressed to mine.

In that minute, with her lips to my ear and her breath warm in the salt wind, Julia said, though I had not spoken, “Yes, now,” and as the ship righted herself and for the moment ran into calmer waters, Julia led me below.

Rarely have I read a scene then made a point of going back and rereading it several times, studying it with such profound reverence. For all the book’s nods to the religion in which I was raised, this one scene reads as a breviary for all I hold holy. The vision of the two of them caught against the rail, the world itself literally throwing them together, Julia and Ryder both trapped, he “warding myself off her with the arms that held her prisoner on either side,” her hair thrown across his eyes — the scene is breathtaking in every sense.

And what’s astonishing is how frequent such passages of beauty fill the novel:

Perhaps, I thought, while her words still hung in the air between us like a wisp of tobacco smoke — a thought to fade and vanish like smoke without a trace — perhaps all our loves are merely hints and symbols; a hill of many invisible crests; doors that open as in a dream to reveal only a further stretch of carpet and another door; perhaps you and I are types and this sadness which sometimes falls between us springs from disappointment in our search, each straining through and beyond the other, snatching a glimpse now and then of the shadow which turns the corner always a pace or two ahead of us.

Everywhere at every stage, Waugh’s book reads as an elegy for love, Waugh himself writing the epitaph on his own doomed happinesses. Himself unlucky in love, as cuckolded as his novel’s many cuckolds, he writes as a coda to the book, “I am not I; thou art not he or she; they are not they.” While true literally, it’s quite clearly as much a lie as fiction ever is.

If there is a better choice to read this novel, I can hardly think of who that might be. Not only did Jeremy Irons act up some serious goodness in the British television adaptation of the book, but his voice, his every inch of person, hangs heavy with a shaggy kind of lingering melancholy, born up with stiff English lip. He has a knack for good characterization, slight accents, brusque types, blowhards, stammering queens, the works. One laments the many, many bad films he’s turned up in latterly, paying the rent pictures and so forth, but here he and his talent naturally shine.

No comments:

Post a Comment