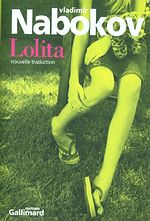

Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov, Read by Jeremy Irons, RH Audio, 2005

There are books about which it is difficult to write. Not necessarily because there is nothing to be said, but because there is too much to be said, and whatever one says is inevitably not enough, is reductive in a way far more injurious to the book in question than others. Such books also produce a raft of lively debate and scholarship and opinion so that what one says has already been said, has already been refuted, has already been retracted, and will likely be seen as insulting, insensitive, misguided, ridiculous, or insightful to one faction or another.

How, therefore, does one solve a problem like Lolita?

While the author sniffed in disdain at a variety of moralizing readings of his text and was just as dismayed at Puritanical types who sought to stifle it, it remains a book that forces you into a variety of tricky mindsets. The first-hand account of how a pedophile steals a small girl’s innocence, childhood, and very identity away from her, a literary game of allusion stacked upon allusion, a model case for unreliable narration, Lolita has been baffling the critics, frustrating the censorious, and discomforting readers since its publication in 1955.

Prefaced with a tricky introduction which gives the entirety of the story away through sneaky openness, the whole text itself is of course a curious document. Meant as a confession to sway the jury in a murder case, Humbert Humbert’s Lolita, or the Confession of a White Widowed Male is in fact a biography and a barely hidden suicide note. Written from both jail and a psychiatric hospital, and released after the death of its author, it is purportedly for presentation to a jury. Throughout, Humbert addresses, both in a literal and ironic sense, the “ladies and gentlemen of the jury” and makes frequent appeals to the reader.

I say “barely hidden suicide note” because I believe that if you should wish to get a judge and jury on your side when accused of murder, it’s really best not to explain that you killed the man because you are a pedophile and the man you murdered was likewise a pedophile but one who stole your underaged lover. It is likewise perhaps a bad idea to consider wistfully the idealized future of impregnating your first underage lover in order to provide yourself with a second down the road a little. These confessions in a law court are unlikely to win you much favor.

Once you get into the memoir, too, outside of the above mentioned facts, it does not take long for Humbert to repel much as he tries to attract with his amusing little ways and his pseudoscientific little asides, his taxonomic rhapsodies, his literary gamesmanship. He is constantly trying to win us to his side, which is interesting from an authorial point of view: an author, who does not wish us to side with his narrator, must at the same time make his narrator as appealing as possibly allowable for the character and mustn’t at any point weight things unfairly against him. And what then does it mean to not stack the deck unfairly against an admitted pedophile?

Nabokov sets the book up so we are forced, if we think at all, to confront several knotty issues. Don’t ages of consent as ranked by region suggest some fungibility in our conceptions of the convergence of physical capacity and mental and emotional readiness? Was not Juliet in that most celebrated of Shakespeare’s doomed romantic couples herself only just thirteen? Is our more modern sensibility stunting development by insisting upon an arbitrary chronological consideration of age, say 18, or is it benevolent protection? Where do hygienic health concerns, as in the Beardsley School’s interest in sexual education as a theoretic, elide into seamier practice, and what precisely separates adolescent male partners into the acceptable realm while placing much older paramours into the category of predatory lecher?

What are we likewise to make of our society’s conflicting demands that little girls grow up and be sexualized while demanding that they stay forever innocent? Or likewise that same barely pubescent objectification thrust upon older women as an ideal to which they must aspire through surgery and depillitation and dieting?

Nabokov rubs our noses in all of this, and the book fairly demands an unsettling accounting in the reader. It is partly for this reason that the scenes of Humbert’s seduction are told in such ripe sensual language. One because that is true to the character of Humbert, but two because it compromises you as a reader. The language and the depiction are erotic, yet it remains, for all Humbert’s romanticizing vocabulary, rape. An indictment of culture’s sexualization of youth permeates the novel, Humbert, as unsettling and as perverse as he is, is our Virgil leading us into a hell of our own making.

One can easily argue that part of what makes the book so compelling and readable is the arising friction between what the author wants and what the narrator wants and how they’re working at partly crossed purposes. And just when Humbert makes you laugh a little or think a little, just when you start to feel an ounce of sympathy toward him, you start guiltily. It incriminates the readership with the creeping occasional feelings of compassion for the villain. If you could reach through the page to throttle the character you would; if he sat across the room from you, you’d demolish him; yet you read on. Isn’t that itself a kind of indictment?

The book likewise begs the question, after a fashion, of what is love. Where (without even considering the age issue) is the fine line that divides predatory behavior from romance? Is it an obsession that only one person possesses? Must it be shared between two to be real? Can it exist for someone as such a maddening passion that the loved object doesn’t even exist save as repository for love? Can we call that kind of emotive projection “love” or must some other word suffice?

Clearly Humbert himself believes in his love. Much like god, though, love exists merely as an item taken on faith. What you say you feel is impossible to verify, just as what you say you believe in is unknowable. Are we to be thrown on the text itself, on Humbert’s account of his behavior, as unreliable as he is both for his self-justifications and for his clearly splintering psyche, or are we to drag in other resources, case studies in pedophilia? If we use the text, should we judge Humbert by his stated feelings or by his reported actions?

Nabokov cleverly uses the first person narrator here, more cleverly than most authors, to obscure such questions, to render such debating points utterly and impossibly unresolvable. All we have in the end is the book and our own feelings, our own revulsions, our own moral compasses. The book then is not so much an indictment of the narrator, but a glass set up wherein we see ourselves in some distorted fashion, in a fashion where we are called upon to judge upon the highest of high crimes, and we are given some rank insoluble dilemmas. It is a house of mirrors.

Part of what makes everything in Lolita so difficult to pin down is that clever mirror structure. The author has neatly written the story with a variety of doubling aspects going on, referencing Poe throughout, placing Humbert’s William Wilson in the character of Clare Quilty. To bring in Poe is particularly clever and allusive, himself the possessor of a child bride.

That Quilty is omnipresent, is within Humbert even, comes out in how frequently there is reference to that first initial of his last name. His mistress, Vivian Darkbloom (a name Nabokov fans will recognize from other books, as well as in other formulations, i.e., Mr. Vivian Badlook, Vivian Bloodmark, and Vivian Calmbrood, all anagrams of Vladimir Nabokov) is the author of a book entitled My Cue. Lolita attends Camp Q. The Gustave Trapp who follows Humbert and Lolita across America by car, is himself a doubling of Quilty, who is a doubling of Humbert.

And it is this mirroring, of author and reader, or character and reader, of character and character, of character and other author, that then begs the question as to the nature of Humbert’s last action as a free man before being arrested. It is the cold blooded killing of Clare Quilty, which takes place years after the he “steals” Lolita from Humbert. It is not the passionate killing in the heat of the moment, it is not a revenge killing during a “rescue” mission. It is a calculated act to some degree, always allowing for Humbert’s clearly fragile grip on reality. When he kills Quilty, when he calculatedly murders his double, what does it mean to him? Who exactly is he killing? Is he killing the baser part of his nature, the physical manifestations of his obsession with Lolita, or is it merely the mark of territoriality? Is it revenge for the years that followed his abandonment? What does this murder signify precisely? Is it, like the book, a kind of sublimated suicide?

Nabokov is too good an author, too intelligent, too tricky to allow us to get off easy with any solid answers. The book itself seduces you into its madness then demands to know what you’re doing there, asking question after question for which no answer will fully suffice. It is a game you can’t win; it is a question you can’t answer; and in asking it, Nabokov puts the reader in the difficult position of asking even more.

Jeremy Irons, who leeringly, creepily filled in the shoes of the most recent film version of Lolita here turns up as narrator, his voice at turns purring with insinuation and at turns quite clearly strained with the emotion of the narrator. It is, to some degree, the role all of Irons’ life has lead him to, and he is better here, far better than in the film, simply because between Nabokov, Irons, and the listener, there is no interference.

No comments:

Post a Comment