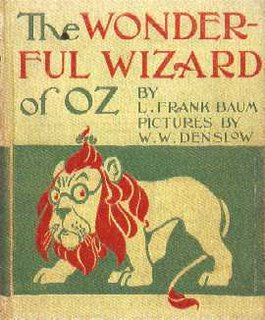

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, by L. Frank Baum, Read by Adams Morgan, Sound Room Publishers, 2001

I’m sure I must have. It seems impossible that it should be otherwise. Yet this much is true.

I have no specific memory of ever having watched The Wizard of Oz all the way through. Not one single recollection.

Once upon a time in the years before VCRs, before DVD players, before downloadable movies from the Web, if you wanted to watch a Hollywood classic like It’s a Wonderful Life or Singin’ in the Rain or even For the Love of Benji, you got one chance per year at best. And if you missed it, you missed it, and it was tough cookies on you, and better luck next year.

Nowadays my three year old can turn on the DVD player, find the right station on the TV, pop in the disc, and set herself up to watch any Hollywood classic we have on hand. Around Halloween, she watched It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown at least twenty times — more than I watched it in my entire childhood.

It is to Hollywood, then I think, that L. Frank Baum’s series of Oz books owe their enduring popularity. I feel confident in saying that even though Baum’s books were best sellers in his age, without those songs, without Judy Garland, without that Hollywood magic, his books would now be curiosities sold in antique stores or republished by smaller specialty publishers as “Lost Classics.”

Which is a roundabout way of saying, Baum’s first Oz book is a bit musty, a bit dusty, and lives forever in the shadow of its best-known cinematic adaptation. It is nearly impossible not to see the now iconic film versions of the characters, nor to gently hear tolling in the brain “Ding dong, the wicked witch is dead!” all the while the text is unfolding.

To be sure, Baum’s novel moves with a surprising speed (especially considering the film’s dawdling 112 minutes) one incident following hard on the heels of the preceding one. Entertainingly enough, Baum starts off his first book with this amusing in hindsight panegyric about “modernized fairy tale” in which he claims:

Folklore, legends, myths and fairy tales have followed childhood through the ages, for every healthy youngster has a wholesome and instinctive love for stories fantastic, marvelous and manifestly unreal. The winged fairies of Grimm and Andersen have brought more happiness to childish hearts than all other human creations.

Yet the old time fairy tale, having served for generations, may now be classed as “historical” in the children’s library; for the time has come for a series of newer “wonder tales” in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale. Modern education includes morality; therefore the modern child seeks only entertainment in its wonder tales and gladly dispenses with all disagreeable incident.

Having this thought in mind, the story of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.

I’m not sure about you, but flying monkeys strike me as pretty far along the nightmarish category of things, as do witches that melt in water, but perhaps that’s only me.

Nevertheless, such predictions are always amusing to those of us years later in the future as we gently ridicule the scientific optimism of the times. How well I remember all the fifties Warner Brothers’ cartoons that promised me flying cars, rocket jet packs, my own laser pistol, and all by the year 2000. Seven years past the deadline and I still can’t disintegrate my enemies at will.

Peruse the shelves at any bookstore and you leave with a hernia-inducing stack of old style fairy tales in which dwarfs, genies, elves, dragons, and the whole lot continue to make merry and impart valuable lessons in virtue. What else is Harry Potter but a barely concealed Christian morality tale chock full of all the stereotypes Baum thought long since passed and done?

At any rate, back to Baum’s nightmares (or my own for that matter), let us ask ourselves why after leaving the hellishness of dustbowl Kansas Dorothy was in any hurry to return. Here’s a gander at the fun and love Dorothy’s missing out on while she vacations among the munchkins (who we apparently mustn’t mistake for dwarfs or anything):

They had taken the sparkle from [Aunt Em’s] eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now. When Dorothy, who was an orphan, first came to her, Aunt Em had been so startled by the child’s laughter that she would scream and press her hand upon her heart whenever Dorothy’s merry voice reached her ears; and she still looked at the little girl with wonder that she could find anything to laugh at.

Uncle Henry never laughed. He worked hard from morning till night and did not know what joy was. He was gray also, from his long beard to his rough boots, and he looked stern and solemn, and rarely spoke.

There’s no place like home indeed.

In fact, there is no fun of any kind in Kansas for Dorothy save Toto, who ends up in Oz with her, so her eagerness to return strikes me as bizarre to say the least.

Certainly Oz is no picnic, what with witches and the strange psychedelica left out of the film such as when The now famous group of Dorothy, Toto, The Tin Man, The Cowardly Lion, and the Scarecrow pass through a china village where everything and everyone is made of china. A fragile world, everything here breaks almost if you cross your eyes. Later in another section, The Lion kills an enormous spider and becomes king of the animals. Okay, nothing nightmarish in giant spiders, I guess.

Though of all the non-filmed parts of the book, my favorite had to be the Hammer-Heads, strange and belligerent “people with shooting heads” whose craniums launch, pound someone, then retract. Far-fucking-out, man. Perhaps all of this stuff is more of those kooky political allegories like the Yellow Brick Road as a metaphoric Gold Standard or something.

All the dated references aside, something kind of surprising struck me. I’ve read very, very old fairy tales, the Grimms Baum so casually tossed aside for instance, and there’s no end to bloodletting in those works. Yet every time you listen to any social critic who bemoans the cruelty and violence in children’s entertainment, they’re always mourning some earlier, Edenic time when children had exposure to nothing but good wholesome fictions.

Within the first two chapters there is an accidental manslaughter by house. When we learn the story of the Tin Man, he begins life as a real man who, in a witchcraft-inspired bout of repeated self-dismemberment, chops off one leg then the other then his arm then cuts himself in half then cuts off his own head. (This is itself a retelling of an old fairy tale.)

Hell, throughout the book The Tin Man frequently uses his axe to hack in homicidal fashion. While being pursued by the monster Kalidahs he chops down a tree bridge they’re crossing, sending them down to their deaths where they were “dashed to pieces on the sharp rocks at the bottom.” At another stage, he chops off the head of a wildcat who is chasing a mouse (that the mouse later turns out to be a queen is incidental). When the Wicked Witch of the West gets wind of Dorothy and company, she sends 40 wolves to tear them to pieces. The Tin Man chops all of their heads off, one after another, and Dorothy wakes to find an enormous pile of severed wolf heads. There seems no end to his bloodlust, though to be fair it is all in self-defense.

Self-defense is no part of Dorothy’s calculations in regards to her mission against the Wicked Witch of the West. At Dorothy’s first meeting with the Wizard, he immediately bargains with her to send her home, but only if she commits murder, that is, he says quite specifically:

“Well,” said the Head, “I will give you my answer. You have no right to expect me to send you back to Kansas unless you do something for me in return. In this country everyone must pay for everything he gets. If you wish me to use my magic power to send you home again you must do something for me first. Help me and I will help you.”

“What must I do?” asked the girl.

“Kill the Wicked Witch of the West,” answered Oz.

To be fair to Dorothy, she resists this plan at first, but it squares poorly with Baum’s introductory comment where he declares that this novel is one in which “the heartaches and nightmares are left out.” A fair number of eleven year olds I suspect might find homicide not to their tastes; “heartaches and nightmares” might even be attendant on such actions, though since waking up in a pile of severed wolf’s heads doesn’t faze her much, who can say?

A similar bargain is made with each of Dorothy’s travelling companions and when they meet after four days have passed and all of them have been solicited to commit a homicide, they compare notes. Pooling their resources and their faults, they decide that they have no real options save to do it. There you go, then. If my options were to stay in a magical land far away from my relatives who never smiled in their tiny shack of a house or murder a witch to return to such a paradise, I think my choice might be pretty easy.

Children’s books, especially classics, generally get a pass on a lot of bizarre messages they impart, the notion being that such books and films are only meant to entertain the wee tykes. That’s all fine and good. I have no beef with pure entertainment. The trouble is that books like this often do provide the very moral lessons they pretend to avoid, and generally it’s some confused hodge-podge like Baum’s tale here.

Further, who could blame a child, steeped in all the values-imparting books foisted on them year in and year out by publishers, writers, parents, and teachers for experiencing confusion when they come to a book that supposedly professes no moral lessons to be imparted, then goes about advocating murder? Baum may have had a knack for story writing that captured the imagination of his age, but he was no profound thinker by any remote stretch of the definition and his tale is a messed up one.

Nevertheless, the story moves briskly, is full of the kind of bizarre activity children generally go in for, yet I still hold that without the film version, only a few people would have heard of Oz lo these many years later. Having finished the first book all the way through, I have no strong urge to read any of the others, but I think maybe soon, my three year old and I are going to sit down and watch the movie version all the way through.

Probably seven or eight times in one month, if I’m lucky.

Sound Room Publishers, part of the general low-budget collectives InAudio and Commuters Library, put out a decent recording here though if judged by packaging alone, I’d never have bothered. Adams Morgan delivers a solid reading here, better than I had expected, his voice clean and crisp and a delight.

No comments:

Post a Comment