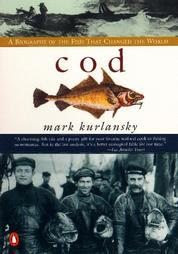

Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, Mark Kurlansky, Read by Richard M. Davidson, Phoenix Audio, 2006

Because the subject is inherently smaller and more specialized, I had suspected that the writing of Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World grew out of writing and researching Salt: A World History. This belief persisted up to the writing of the review of Salt when I discovered my mistake. One naturally thinks of the smaller growing out of the larger.

Not that Kurlansky isn’t just as assiduous in cramming his book with enough historical curiosities to keep you reading. Both books rate very highly on the trivia per page scale, and Kurlansky strings this sort of stuff together so wonderfully, I rather suspect he’s received some tempting offers from The History Channel to spice up their usual fare of Hitler vs. Stalin black and white footage. You’ll know they’ve co-opted him when Panzer: An Intimate Look comes out in time for Sweeps Week.

Nevertheless, Cod differs in one major respect from Salt in that the former actually goes about informing you what the environmental state is today — and it’s not a pretty picture. Over fishing has thinned the ranks of the species, leading to younger maturation which leads to ever smaller fishes, while pollution and rising ocean acidity and temperatures have limited natural spawning grounds.

Kurlansky starts his book in modern day Newfoundland, what he calls "the wrong end of a thousand year fishing spree." It's a good start. We see how things stand, we see the results of what Kurlansky will back up and show us when everyone cried out for cod.

We go back to the nine hundreds and discover that what allowed the five documented voyages of the Vikings to Canada and possibly Maine was their ability to salt their cod. But it was also the fishing of the cod that lead them further and further afield. Voyage accounts from the Vikings noted ever richer cod fishing-grounds as the ships sailed west of Iceland. This is seconded by John Cabot's claim of the lands he sailed to, Newfoundland, for Britain, where he noted its richness most specifically by documenting the abundance of cod in the waters nearby.

Many suspected at the time (and still do) that these abundant waters were at the heart of the Basque riches. This tiny ethnic minority in between Spain and France (also subject to a history by Kurlansky) managed to find cod in the Atlantic when every other country was having difficulties. The sheer quantity of their catches gave testament to a heretofore undiscovered cache, though the secret was never given up by the wily Basques who amassed great wealth for some time.

Of course, anything good, you just know the British are going to want a piece of it. And it isn’t long before they’re casting about for places to expand. The British Naval Empire officially began with two blows against Spain, weather destroying the Spanish Armada, while the British navy attacked and sank the Spanish fishing fleet. And once they got into the cod business, they immediately began codifying much of their naval laws around it. Trading laws in England eventually forbid trading cod with other countries. Expansion to the colonies often hinged on fishing.

What was the name on the map that so enchanted the expatriate Puritans holed up in Amsterdam as they squinted at possible avenues for their next destination? A small curl of land known as Cape Cod. To hear of their travails is to hear of a series of small-minded jackasses who would have starved were it not for their ability for stumbling across Indian food caches. Even with cod practically there for the grabbing straight out of the water, these settlers bumbled almost as badly as the incompetents at Jamestown.

The prevalence of cod was so notable that cod was on the state seals of the early colonies, many of the first American coins had codfish on them, as well as a 2 penny tax stamp. Codfish aristocracy who could trace their lineage back to the seventeenth century decorated their mansions with cod designs. A wooden carved cod in the Massachusetts congress followed it from one locale to the next, including one transfer in which the sculpture was wrapped in a flag and ceremoniously carried and greeted at its new habitat with applause.

It almost is possible to say that America would not have been a going concern, would not have had the riches to stand up to England, nor to become the economic powerhouse we once were were it not for cod. The fish market was a powerful New England engine of finance while the cod, dried and salted, was a plentiful source of protein to keep African slaves working the eighteen hour days for cane and cotton plantations. There were three ways to buy slaves in West Africa: cash, salt cod, or rum.

As unsavory as the last two points are, it is important to understand how much slave labor contributed to America’s economic growth. Between slaves and cod, the world would be today a remarkably different place had not America been built upon them.

America might not have been itself either if negotiators had worked a little harder settling differences between the colony and the mother country. In the run up to the American Revolution, the colonists and the British were working out various trade issues trying to calm the waters of revolt. The hardest New England sticking point was the fishing grounds rights.

England apparently learned nothing from all of this and continued to play the role of provocateur internationale when it came to cod. The establishment of the now familiar International Waters came about as a result of Iceland’s fishing industry’s rebellion against Britain’s frequent incursions into what they considered their territorial waters.

In the single generation from the beginning of World War One to the end of World War Two, Iceland managed to achieve full independence from Denmark (it had been a colony previously) and to grow significantly into a modern European state. It was the mouse that stood up to the lion as Britain again and again refused to honor the fledgling nation’s demands that its ships respect its boundaries. The bigger island nation had the nasty habit of sending large whaling fleets through, enormous nets slung below, sweeping the entire ocean before it clean of fish.

Over the course of the last fifty years, the two nations have been involved in what are termed the three Cod Wars, a series of naval escalations that involved at one point gunfire and repeatedly ship ramming. Each war began when Iceland extended its national waters first from three miles (the international standard at the time) to four, then from four to fifty, then from fifty to two hundred. Each time, only the British choose to break this line. NATO itself got involved to arbitrate the dispute. At one point, Iceland even broke off diplomatic ties with England.

Kurlansky’s book is a fascinating history that leaves no stone unturned but is without pedantry or much in the way of tiresome extraneous information. As a vegetarian, I was less than enthralled with the book’s bevy of cod recipes, though I can see how they’d be of interest to the vast majority of readers of this book. It may lack the zing of reading about the Cod Wars, but it is part of a well-rounded portrait of a fish, a biography far more interesting than I might ever have believed possible.

Richard M. Davidson reads and two weeks after listening to his performance I have to admit not even the trace of an accessible memory remains. You may take that as either a good sign or a bad one. I’m sure I don’t have a clue anymore.

No comments:

Post a Comment