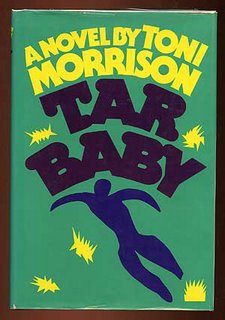

Tar Baby, by Toni Morrison, Read by Lynne Thigpen, Recorded Books, LLC, 2000

“Didn’t the fox never catch the rabbit, Uncle Remus?” asked the little boy the next evening.

“He come mighty nigh it, honey, sho’s you born--Brer Fox did. One day atter Brer Rabbit fool ‘im wid dat calamus root, Brer Foxv went ter wuk en got ‘im some tar, en mix it wid some turkentime, en fix up a contrapshun w’at he call a Tar-Baby, en he tuck dish yer Tar-Baby en he sot ‘er in de big road.

….

“Brer Rabbit come prancin’ ‘long twel he spy de Tar-Baby…”‘Mawnin’!’ sez Brer Rabbit, sezee--’nice wedder dis mawnin’,’ sezee… Tar-Baby ain’t sayin’ nuthin… Brer Rabbit keep on axin’ ‘im, en de Tar-Baby, she keep on sayin’ nothin’, twel present’y Brer Rabbit draw back wid his fis’, he did, en blip he tuck ‘er side er de head. Right dar’s whar he broke his merlasses jug. His fis’ stuck, en he can’t pull loose. De tar hilt ‘im. But Tar-Baby, she stay still…

“‘Ef you don’t lemme loose, I’ll knock you agin,’ sez Brer Rabbit, sezee, en wid dat he fotch ‘er a wipe wid de udder han’, en dat stuck..”

From Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings.

The title of Toni Morrison’s sizzlingly bitter 1981 novel Tar Baby comes partially from Harris’ story quote above and also from the idea of the tar baby, as well as the term as racial slur, as it has entered popular conception. It’s kind of a strange choice as a very large percentage of the novel doesn’t immediately concern itself with the characters who specifically cite the story specifically. Certainly the character who falls into the trap in that dynamic becomes stuck in a souring relationship that blossoms under (to say the least) strained conditions, but since so much of the book focuses on other characters in his vicinity that more symbolic resonation is going to have to signify here.

The novel tells of six people at the winter home of Valerian Street on the Caribbean hide-away of the Isle des Chevaliers. Street is the heir to the Street family chocolate fortune (itself a kind of ironic joke, the white man made wealthy by brown sugar) and married to the decidedly mental Margaret, former white trash Miss Maine. His butler Sydney is married to the cook, Ondine, and together they raised their orphaned niece Jadine, who sometimes acts as Valerian’s secretary (as well as off and on model), a kind of indentured servant since Street paid for her college.

The five of these characters are on the Isle des Chevaliers waiting for the possible Christmas visit by the Street’s only child, their son Michael. Instead of his visiting, they discover a man who has been living on the property for days after having jumped ship, the convict Son Green. Son’s appearance shocks the entire family, but even more so are they shocked by Valerian’s invitation that the man stay with them, continue living there. Oddly taken by Son, Valerian uses him as a distraction from the coming explosion building up within his wife at her son’s absence.

There is an element of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf to Margaret and Valerian’s marriage, Michael being a long absent sort of cannonball they routinely lodge at each other. Morrison zeroes in on various things that take place in a fighting marriage: the way small irritants serve as a pretext for lashing out for other, darker angers. One agitates one’s spouse to the point of his/her reacting which provides the opening for escalation. Each of Morrison’s fights are choreographed with this rather common tactic, and her skill in the categorical rise in temperature makes all the fights feel organic. Valerian’s proposition to Son to continue living there constitutes a kind of dodge in the hostilities, using Son as a distraction and as a stand-in for his real son, but the man’s presence is considerably less of a salve to the others.

Ondine and Sydney are offended at Son’s appearance and his past at first, shocked by his low-class ways in relation to their dignified upper class servant status, seeing him as trouble and a kind of interloper. Margaret, a gentrified Maine cracker, is terrified of Son, his exposure to the family who he’s been living off taking place in her closet in her bedroom. Son had been sneaking through the house at night, stealing what food he could find, and his appearance in Margaret’s boudoir conjures in her all the hoary stereotypes of sex-mad black men raping white women.

It is with Jadine that Son’s presence is the most unsettling. It is evident early on that there is sexual magnetism in both directions, though Jadine believes she rests comfortably miles above the cruder convict. She has lived in Paris and New York, lounges about naked at times save for a baby seal fur, and has had the best education Valerian Street’s money can buy. The attraction between the snooty and refined college girl and the rougher edges of the real man of the street is somewhat of a cliché, but Morrison grapples tightly with it. A cliché in her hands is never a tired old stock situation, but a chance to explore what has made the cliché so common, so important to us.

Reading Toni Morrison is tricky, like going to a party where everyone knows everyone else but never deigns to introduce themselves and you want to join the group. All kinds of secrets stir underneath, all kinds of past resentments simmer below the surface, all sorts of battle lines have already been drawn. One of the elements most remarkable about her storytelling is that she can write one scene in which a character is quite awful to another. You can honestly hate that person quite strongly. A second later, she can be telling a scene sympathetic to that exact same character and something in the way s/he thinks or acts or cries can make you suddenly warm to the character. It is a constant unpacking of one section of a personality, only to have it destroyed by the unpacking of another part, which will in its turn be destroyed.

In media res is typically used to describe a novel in which you come into the very middle of the action, Odysseus’ tale pausing to get the back story in large chunks. It could also equally apply to Morrison’s writings; we have walked into the middle of an argument of two people we don’t know. There is no guarantee that we will get enough in the flashback to fill us in to make fair judgments. Instead, we constantly play catch up, Morrison doling out bits and pieces, just enough to keep us dragging along, never enough for us to catch up completely. There is usually at least one more piece to the puzzle, one final, important piece, that we will only come to understand in the book’s final chapters.

There is one here then too, a secret so monstrous that it shocks the entire “family” dynamic and breaks apart this group of six. As in other books by Morrison, ghosts are an element of them, partly real, partly a figment of people’s imagination. The absent son himself, though living, is a kind of ghost, the late revelation as to why he stays away brutally shocking, unexpected but with the natural unfolding of believability. It sets ups the question, how do you deal with the fact that your spouse has been a vicious monster — and you never even realized it, even though there were behaviors that seemed wrong to you for years and years and years? And the following, less considered but somehow worse question, how do you later come to terms with the reality that the monster is only a part of that person, one part, not the whole? It is a heartbreak that is so strong it brings bewildered disconnection from reality.

Part of this shockwave sends Jadine and Son away from the island where they first try to live in her world, then go to visit his, in the small country town of Eloe. The friction between the backwards conservatism of Son’s upbringing and the business minded, modern rootlessness of Jadine’s cosmopolitanism ultimately shatters them as well. Jadine is both attracted to a kind of primal blackness Son represents, as well as the elusive dreams of success and acceptance presented by the white world of wealth with which she grew up and associated. Son is himself trying to come to terms with the obligations of family and how it jars against one’s own dreams and desires.

In the toxification of their relationship, Morrison explores the frames of identity, black pride, white identification, male and female expectations, and the definitions of successful. At times it seems as if Jadine is the tar baby, a carefully built type of trap for Son, and at other times it seems as if the trap is the ideal of life Jadine aspires to, the one presented to her by Valerian. Morrison is able to navigate these tricky waters without ever coming down clearly on one side or the other of a multitude of issues, leaving it to her readers to sort out their own rather complex feelings on race and sex. The tar baby is our own notions of race, it is the baggage we have brought with us, the baggage given to us. It is our own limitations that trap us.

And this is where Morrison stands head and shoulders above so many others who try their hand at writing about charged social issues. She recognizes their inherent layers and levels and at times points the finger of blame at everyone involved. In this she reigns, never stooping to outright the feel-good propaganda of it all being whitey’s fault, or men’s fault, or women’s fault. It is everyone’s fault and everyone’s burden. And if the Streets aren’t overtly racist in behavior, they exist in a world of certain racial expectations. No less so than the likewise very specific racial expectations Jadine and Son and Ondine and Sydney occupy.

This audiobook languished on my shelf for all three of its library renewals. I always said, soon, soon. But the truth of the matter was that I was frightened of the book, of reading it. Reading Toni Morrison at any point is work, or at least I kept telling myself that. It is occupying reading, of the kind that makes you think, that stirs your conscience, your mind, and sometimes it is easier to tickle the brain with less weighty works. Which is a notion I find ridiculous once I actually start reading (or listening to) a Toni Morrison novel because for all the work she makes you as a reader do, there is never anything unpleasant about doing it for the reader. It is work, yes, and it sometimes challenges us to think about our own trickier psychologies, but it is engaging work, fulfilling work. It is not the drudgery of having to chase down literary allusions nor the psychological profiling necessary to understand abstract behavior.

Morrison reminds us over and over that good literature, hell, good fiction without having to carry the baggage of capital-L literature, can be enjoyable as well as edifying. It is a lesson it seems we have to learn and relearn with every waking day with any number of pundits, professors, and practitioners of art striving so hard just to make the quite opposite point.

Lynne Thigpen, best known to many for her Carmen San Diego work, is an able reader if a sometimes affectless one. Her voice is clear and strong, but it works to maintain its evenness when some scenes call for things to get a little raggedy. Her vocal characterizations aren’t particularly strong, but Morrison’s writing is crisp and clear enough that even in long scenes of dialog the speaker is never in doubt.

No comments:

Post a Comment