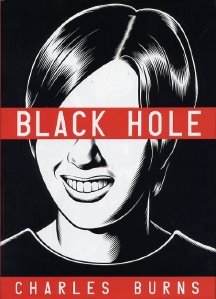

Black Hole, by Charles Burns, Pantheon Books, 2005

When I read a short review of Charles Burns’ new graphic novel, Black Hole, the description of the work it proffered (quoting from the book’s jacket: “the mid-1970’s…a strange plague has descended upon the area’s teenagers, transmitted by sexual contact.”) made me wonder if the man ever wrote about anything else. When I later read that he’d spend the better part of the last ten years writing and publishing this work in a serial format, I realized that I’d probably read portions of it over that period.

Which is not to say that apocalyptic scenarios involving teenagers and sex isn’t something of a theme that runs through Burns’ work. In a world in which authors routinely retell the same story, this is not a particularly distressing thing. It only means that unless you share the author’s particular obsession or bent, a little can go a long way.

Nevertheless, when I happened to walk past Black Hole at the library with the bright yellow “NEW” sticker on the cover and realized that it was just sitting there, no one was snatching it up, I did exactly that. Clocking in at 368 hard back novel-sized pages, Black Hole continues to demonstrate that the graphic novel field is a rich field in which only the topsoil is regularly tilled by leotard clad fanboy books of the Marvel sort. New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl is all full of hot air in declaiming that this art form will stagnate and slide down hill in the aftermath of the blistering comet that was (and is) Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan.

(As a side note, Ware’s Acme Novelty Library, while it appears at first to be a disconnected collection of random pieces from his own comic, is in fact further proof of exactly how much open space there is in the realm of graphic novels. They have as much room to grow as novels have, but have only stuck about one foot into that particular hokey-pokey. Ware’s collectibles collectors in that latest work are presented to us in mostly unconnected vignettes, the sum definitely larger than the parts, as we watch a friendship, and one collector’s mind, disintegrate completely. As loathsome as one character is, flashbacks to his childhood often have that bitter tang of sympathy you sometimes feel for monsters.)

As the jacket quote goes from above, Black Hole takes us back to the 1970s in suburban Seattle. For some time at the book’s beginning, a plague has been working through the local teenagers, passed through sexual contact, which mutates their bodies in peculiar and different ways. One girl grows a tail, a boy’s face melts into just a skull shape with eyes sunken back into the sockets, bulbous growths develop, tentacles, and other such mutations.

We follow through this story mainly a quartet of teenagers. Keith is a young boy who falls in love with a girl named Chris in his biology class. Chris is in love with Rob who she meets at a party. Rob is in love with Chris. Keith later falls for Eliza (the girl with the tail). Rob, of all the characters, has the most haunting of deformities, and perhaps one of the easiest to hide. Just at the base of his throat is a small mouth, with teeth, tongue, and a tiny, tiny voice. We find, through the course of this book that the mouth speaks as if in prophecy, the various little things it says being repeated much later on in the story, at moments where those words become clear.

And there are moments like that all through the work, little phrases said by one character that turn up again in unrelated places, the book echoing constantly. We start about halfway into the tale and then fill in the rest through flashback and as we do, things said, lines that appeared just filler dialogue take on deeper, darker meanings.

While the clear metaphor for AIDS runs through the story, Burns’ interests aren’t simply for drawing clear parallels to our own society in such a specific way, but focuses more on the idea of infection as a kind of social ostracism. Once infected, the teenagers aren’t rushed by their parents to the hospital and no one at any point in the story speaks of a cure. The one sadly amusing parallel that does turn up is when Chris, after having become infected and gone to live out in the woods where others like her live, wakes an old school friend at home to use her shower. As they sit and catch up, Chris is repulsed by a Halloween photo of her friend and her boyfriend with Bowie make up on, Bowie being too strange and transgressive for some at that point, even for a girl who molts and sheds her entire skin.

Burns’ story then is a nightmarish vision of high school and early college, on conformity and deliberate isolation, and a sideways exploration of the pain we all suffer in growing up and growing apart. It is also a tail of doomed love, of psychotic obsession, and a recollection of that heady drug induced decade where all the promises of the sixties’ flower children turned twisted and repulsive.

Relying heavily on dark lines and shadows, Burns’ art has a kind of expressive broody quality that quickly moves into phantasmagoric. There is a purity in his lines and his framing though that grips you whether it’s mere outlines in shadow or fully detailed renditions of a tent in the deep woods or the caverns the plague has carved through one boy’s face. There are pictures exuding an intense realism (the endpapers’ run of yearbook style pictures is one instantly recognizable page) and others that seemed carved on a chimerical woodblock of nightmare and bad acid. It is indeed a talented man that can pose a naked tailed woman in just such postures as to be still arousing, then turn around and draw a mutant hand holding a chicken bone bit in two with such a revolting degree of specificity.

Burns’ earlier work may indeed be prone to the ridiculous and the absurd. Black Hole, on the other hand, is a work of mordant sympathy that hooks our hearts rather piercingly, alternating between the grotesque and the tragically commonplace. From its opening pages of a frog dissection to its desperately quiet and strangely beautiful yet suicidal conclusion, Burns captures the distilled essence of teenage heartbreak and fear and renders up a work that demands to be read and reread and reread again. Black Hole will suck you in.

{Most of the links are to samples of Burns' artwork, which you really owe it to yourself to check out.}

No comments:

Post a Comment