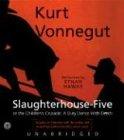

Slaughterhouse-Five: Or The Children’s Crusade, A Duty Dance With Death, by Kurt Vonnegut a fourth generation German-American now living in easy circumstances on Cape Cod and smoking too much who, as an American Infantry Scout, hors de combat, as a prisoner of war witnessed the firebombing of Dresden, Germany, the Florence of the Elbe, a long time ago and survived to tell the tale., Read by Ethan Hawke, Harper Audio, 2003

Breakfast of Champions: Or Goodbye Blue Monday, by Kurt Vonnegut, Read by Stanley Tucci, Harper Audio, Inc., 2003

Breakfast of Champions: Or Goodbye Blue Monday, by Kurt Vonnegut, Read by Stanley Tucci, Harper Audio, Inc., 2003“We are healthy only to the extent that our ideas are humane.” — Kilgore Trout

How, exactly, does one go about critiquing an obvious and well-regarded classic about which the author states quite directly in the first chapter that he considers the book a failure? Slaughterhouse-Five is, by Vonnegut’s own admission, a washout if one considers it to be about the Dresden bombing, its putative subject. Certainly that horrific incident is the backdrop for much of the story, the frame around things, the touchstone upon which the rest of the story relies, yet the novel isn’t really about the Dresden bombing at all. Therefore, Vonnegut is correct when he says that as this is his book about the Dresden bombing, in its efforts to address that event, the book fails.

Which is, of course, no standard by which to judge a book. Authors’ own opinions of their work can be counted on to be unreliable through and through. Still there is a grain of truth to that judgment, especially if what Vonnegut means is that the book did not perform certain traditionally artistic cathartic duties. To read the output that follows Slaughterhouse-Five it’s clear that Dresden, the horror of it, the magnitude of it, is something that Vonnegut is unlikely to ever escape. And so on that level, perhaps the novel is also a failure at being palliative. Yet Slaughterhouse-Five is concerned with more than simply making its creator feel better.

What the novel is about instead is a particularly American kind of stoicism, a wry riff on Marcus Aurelius, determinism, and acceptance of what fate has in store for you. Billy Pilgrim, the novel’s hero, as we all know, has come unstuck in time. The constant journeys his unmooring visit upon him allow a perspective on time that goes beyond even the emperor philosopher’s ideals, destroying what little faith he could have had in the concept of free will. “Among the things Billy Pilgrim could not change were the past, the present, and the future,” one of the novel’s primary codas is simplified even more so in the book’s immediate successor, Breakfast of Champions, writ simply as “Everything is necessary.”

And, as Slaughterhouse-Five is partly, I suspect, an attempt by Vonnegut to come to terms with the Dresden ghosts, it forms, in this reviewer’s perspective, a related thematic threnody with Breakfast of Champions, Vonnegut’s novelistic grappling with his mother’s suicide. Taken together, these two traumatic events have shaped Vonnegut, haunted him, damaged him, and produced the two novels that sit in the middle of his career as a raw and bleeding central heart. They are both terribly funny at points (on all that phrase’s oxymoronic levels) while burning with the low flame of bitterest depression.

Much like Slaughterhouse-Five, Breakfast of Champions is also, according to Vonnegut in the book’s first pages, a failure of a book. This is how he feels apparently about all of them, a kind of post-writing depression clouding his critical faculty. Breakfast of Champions, if judged by traditional dramatic conventions, is a much more successful novel than Slaughterhouse, following a bit more cohesive narrative compressed to a much tighter frame of action. And yet, it is somehow less rewarding and fulfilling than its more spectacularly failing predecessor. Part of this is the slight carryover, like the “And so on” turns of phrase, and part of it could be the result of the Dresden novel draining Vonnegut so much, leaving him little left over to attack his suicide/mental illness fears.

Following “two lonesome, skinny, fairly old white men on a planet which was dying fast,” Breakfast tells of middle-aged Pontiac dealer Dwayne Hoover, who is losing his mind, and how his collapse is completed and exacerbated by recurring Vonnegut protagonist Kilgore Trout, the nearly totally obscure pulp science fiction writer. Trout works as a Vonnegut stand-in, channeling any number of the author’s philosophical conceits in rather poorly conceived but often hysterical sci-fi allegories. Trout makes an appearance of sorts in Slaughterhouse, though more off stage, his novels acting as catalysts in some scenes, and he is as omnipresent in Vonnegut’s work as Dr. Benway is in Burroughs’ (though without the sinister aspect).

The strange closing scene of Breakfast following Dwayne Hoover’s psychotic breakdown, where “Kurt Vonnegut” the character in the novel approaches Kilgore Trout is the most important moment of the book, it is the novel’s real climax. The rather “dramatic” action preceding it functions more as a literary convention, while it is the bleak last pages in which Trout begs for youth that give the book its true stab. It is the cri de coeur of the author on his fiftieth birthday, an old man harkening back to his youth in Indiana, a period of his life to which Vonnegut obsessively returns. It is fundamentally clear that this era, pre-Dresden, pre-death of his mother, represents a kind of Edenic time even if Vonnegut is wised up enough to see through such illusions.

While the four preceding novels (save Cat’s Cradle) were more structurally coherent and followed more literary dramatic conventions than these two, with the sudden step off into experimentalism, with the injection of his own role into the narrative thread, with the blurring of fiction and personal reminisce, and with the increasing size of the philosophical asides, Vonnegut in these two novels most fully becomes the person of which we think when we think “Vonnegut.” They are both the peak of his writing, and its point of no return, the novels that come after pale shadows of the vivid interplay of ideas herein. While Vonnegut revisited many of these characters, it is the ideas that he was unable to let go of, the apocalypses, the far into the future accolades, the final bitter turn of the worm.

Actor Ethan Hawke’s reading is marred by two evident flaws. The first is that he apparently feels the novel is a secret that we need to hear about in a very soft little whisper; the second is that he finds his voice oh so sweet and wishes we should just roll around in its soft furriness like he does. We can be thankful he limits his characterizations to the faintest of sketches of vocal inflection. Hawke clearly considers the book “Great Literature” with all the pompous seriousness that entails—and this is the opinion of someone who genuinely likes Hawke as an actor.

On the other hand, actor Stanley Tucci’s reading snuggles in your ears and is ever so lovely. He’s just a maddeningly talented actor, intelligent, a good writer, as well as a hysterical comic. Here he reads without trying too hard to “act” the parts and the resulting effect is a pleasant experience, far more enjoyable than Hawke’s at-times distracting husk of a voice. Both readings are filled out with short interviews of Vonnegut by his long-time friend and lawyer, Don Farber, reminisces humorous and illuminating, though only Slaughterhouse manages to tack on an annoying dance mix electronica number featuring snippets of Vonnegut’s now-classic renderings of the book. Tastefully tucked on at the tail end of everything, it is easier passed over and even more easily forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment