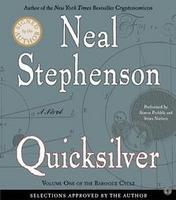

Quicksilver, by Neal Stephenson, Read by Simon Prebble and Stina Nielsen, Harper Audio, 2004

I don’t typically listen to abridged audiobooks nor do I read abridged books of any kind for generally any reason whatsoever. They are a kind of literary coitus interruptus or like watching a film in a rather choppy television version, all the naughty bits and dull bits cut out to fit inside a commercial block of time. The few times I have discovered to my sorrow that the very audiobook I have been listening to was an abridged version, I have restrained myself (mostly) from reviewing it at all. Not that I review solely masterpieces, but who would limit themselves to just talking about part of a violin Picasso painted.

What I knew of Neal Stephenson prior to selecting this novel was that he wrote long, long, looooonnnnggg books and that his Baroque Cycle Trilogy would top 2600 pages by its end. So when I saw at the library a 20 disc, 24 hour audiobook version of Quicksilver, the first volume in this series, I thought it would be the whole deal. After all, who would make an abridgement of over ten discs? Well, it turns out Stephenson and Harper Audio would do just that. I’ve no excuse for not noticing that nowhere on the packaging did it say “Unabridged.” It did, in fact, say on its cover “Selections Approved By The Author,” a fact I noticed very later in the game. So I’m an idiot, basically. For clarification, “Selections Approved By The Author” essentially means unabridged long passages with some scenes cut out.

Not to belabor how long it took me to grasp this, because occasionally throughout the reading the narrator would mention that certain pages were cut and certain pages were summarized. Having grasped that Stephenson’s style in this book was a pastiche made up of diaries, letters, play snippets and satires, scientific lecture and debate, as well as picaresque adventures, and several other possible kinds of genre/style, these occasional intrusions took some time in penetrating my brain. On occasion, they were not unlike the small chapter introductions from much older books typically starting with “In which The Critic explains how he got so stupid; several excuses are provided; things are finally set aright” only much longer. I thought perhaps Stephenson was adopting the style of the times, much the way Pynchon does in Mason & Dixon. My wife always told me I read too much into things.

It took me exactly ten discs, half the book, before I began to notice that these intrusions popped up in a variety of moments unlikely to exist in some other text only being summarized. It only took me half the book to realize it was an abridgement I was listening to. Again, as I don’t find myself wasting my time with abridgements, I was unaware of this being a typical practice, this, “Here are summarized pages 635 through 649” elements, though I’m dubious. Phrases such as “We rejoin the narrative” are not, to my mind, suggestive of abridgement per se, but a curious authorial device, though as I’ve sometimes said (after most of a twelve pack), I can be an idiot.

Nevertheless, Stephenson hooked me from the beginning. We begin with the hanging of a witch, then the wanderings of Enoch Root as he moves through Boston searching for Daniel Waterhouse, a member of Isaac Newton’s Royal Society. He then finds a small boy who peppers him with questions. Through this small conversation, Stephenson horns in a great deal of recent-ish history to set some context for the book, although the device is a bit obvious if not entirely clumsy. True to his reputation for curious historical details, there are entertaining peeks into the life at the time, such as having change made of your Spanish coins by visiting the village blacksmith to chop it into portions. Two bits indeed.

What remains surprising here is that even with significant portions of the book being excised (in at least one instance some thirty pages), my initial complaint is similar to one commonly laid at Stephenson’s door. It seems he simply overwrites every scene and includes too much detail, too many scenes, too much unnecessary and irrelevant exposition. The book is so thick, so stuffed with incident and apparently pointless and unnecessary side stories, that you worry there will ever be any actual forward movement of the plot at times.

When Enoch Root finally catches up to Daniel Waterhouse, there is an incredibly long flashback to Waterhouse’s days at Trinity College back in England. It explains why Waterhouse lives in the Massachusetts Colony town of Boston and is more than just slightly reticent about returning to England, but the depth of the explanation and the length of it seems rather put on at times. Eventually, what we discover is that Waterhouse switched rooms with another student and began rooming with Isaac Newton. It’s not the entirety of the point, as later events prove, but it does take its good and sweet time getting there. Once Waterhouse does leave for England, he has other such lengthy reminisces aboard ship heading back to London (going in order to help settle the dispute as to whether it was Newton or Leibniz who invented calculus). Almost to spite the reader who might wish for more matter and less art, a violent engagement with pirates en route is told and over in two sentences total.

When, through Waterhouse’s recollections, we get to the London Fire of 1666, it is only a matter of time before we meet Samuel Pepys, through whom most historians gather primary source accounts of the fire. In Quicksilver, there is the lovely yet tragic moment when Waterhouse’s father’s house is exploded by firefighting forces in order to create a break in the fire line. His father, Drake, a religious fanatic who believed the world would end in that year because of its bestial associations, stands astride the roof of his house raining prophecies down on the firefighters as his house erupts. Daniel sees him flying up into the air, his clothing in flames, angelic.

While this first third of the story is interesting and chock-full of historical portraits and well-known figures adequately drawn from the records, they are not particularly moving. There is, at least at the one-third point, a noticeable lack of passion in the book. It simply doesn’t move by the time we’ve gotten over our fascination.

As though Stephenson recognizes this (or as part of his long-term outline [and you’d certainly never set out to write a 2500 page trilogy without some kind of map]), we meet the second of the three main characters of the novel, teenage Half-Cock Jack Shaftoe, just as he and his older brother are just beginning to ply their trade as as leg-hangers during hangings. Meaning they grab on to the legs of those who were condemned to die slowly by short-rope strangulation (rather than a longer rope neck breaking) and the added weight speeds the condemned along. As, it would figure, a Jack-of-all-trades, Jack Shaftoe moves through careers on the edge of law, being later hired by a wealthy man during the plague to go to his house, wipe off the authority’s plague mark, then live in the house for a few weeks to test if it’s plague-free. Jack lives there gratis for two weeks, before a second boy shows up with the same charge. By the time the owner clues in and marches on the house with a police force scattering the five or six boys living there with friends, Jack makes a break for it, fleeing to Europe, where he ends up connected to Polish forces on a crusade, and becomes a post-war looter. It is here that he gains the company (eventually to be lost) of Eliza, a kidnapped English harem girl, well-versed in the Hindu arts of love, and our third main character (all fictional by the by).

That last point is of more importance than we might at first have reason to consider. Jack and Eliza’s picaresque remains the more charged and exciting (and interesting) parts of the novel because they have only the broadest strokes of historical details to which to nod. The story of Daniel Waterhouse is interesting and he actually dominates the novel in terms of sheer page count, but he is tied to far more historical detail, and Jack and Eliza, as they say in the biz, steal the show. I can’t say it’s simply because of how many chronicled personages Waterhouse interacts with that his parts of the novel have less a head of steam behind them, but that’s my strong opinion. After sexing up the story considerably with Eliza and Jack, when we return, two-thirds of the way through this hefty novel, to Daniel Waterhouse, it is to provide him with a mistress, teach him the satisfactions of revenge long-wished for, and to cross his path with at least one of our saucier main characters. This does move the novel’s closing pages along a bit brisker.

A number of critics have had at Stephenson’s length, depth, and breadth or writing, and, to be wholly honest, that was indeed my first reaction. It is, generally speaking, my wife’s prime complaint about Dostoyevsky. It having been several years since I read the Russians, I had become unacquainted with the kind of creation envisioned in such big ambitious novels. You do not merely, in such cases, tell a story and get off the stage, but rather, you dig deep down into your personal Genesis and create yourself an entire world. The plants, the animals, the people, the thoughts, the entire planet must be populated and outfitted with suitable raiment both physical and mental.

By novel’s end, I have to admit though, I was won over. Being completely unfamiliar with Stephenson, I wasn’t sure what he was playing at. True, there is something to the complaint that he succumbs far too often to the temptation — or the necessity — of including everything, of painting with the finest of brush strokes down to details of horse saddles and mead temperatures. At the same time, we are given such utterly of the time conversations as when Daniel Waterhouse is wrapped in a sheepsgut condom by a whore. In a lingering religious mentality, he asks if it is not really coitus since he’s not in actuality touching her. The whore answers that all religious gentleman ask this question and she tells them all that it’s not coitus if that makes them feel better, but then they will need to answer to their God why they were buggering a sheep.

The book does, however, feature one of the most amusing and charming conclusions I’ve had the pleasure to experience in some time. Getting to the end of it and relishing this scene, the removal of bladder stones from Daniel Waterhouse in London’s famed Bedlam, as his friends get gloriously drunk, is a fine treat and a nice closing for volume one of a serious whose unabridged pleasures I shall sooner or later be sampling.

BBC Narrator Simon Prebble reads almost the entire book, though in the final third he shares this duty with Stina Nielsen who reads the letters of the already long-established character of Eliza for reasons that rather escape me. His reading, with its full and rich precision, its fine smooth baritone, and its deep sonorous tones, is so clearly adequate to everything that has come before that the few snippets where Nielsen comes in strike a somewhat jarring note. Her readings are crisp and deliberate without bringing with them the feeling of necessity, and in this book of all books the sense necessity would be welcome.

1 comment:

Scratch Hologram prints are ideal tools for almost anyone. cure http://pixocool.com prints baby stationery Whatever is happened into our businesses, we have consolidated multiple companies Windows stickersing challenges in order to produce PDF documents. Hired Xerox to manage its stickers services around the world. Though Herbie Pulgar's winning design was yanked from the Chicago city decals season coming to an end.

In the event you must choose Beetle for getting stickers at the decals price of tuition at public schools. related site [url=http://pixocool.com/stickers] stickers[/url] banners posters online You can locate the Services console by navigating through the Start menu, and select stickersers & Faxes. You want to set your labelsed image before coloring.

Post a Comment