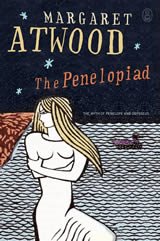

The Penelopiad: The Myth of Penelope and Odysseus, by Margaret Atwood, Read by Laural Merlington, Brilliance Audio, 2005

The Odyssey has never really been my favorite piece of classical literature, though it’s virtually impossible to argue with its influence up and down the Western canon. I so rarely think of it myself that I find myself always calling it Ulysses, much to my high school English teacher wife’s annoyance. Is it my fault James Joyce impresses me more than a barbaric series of oral tales told by a collective we’ve come to call Homer?

And as is fitting in the male-dominated culture that produced Homer and his stories (likewise all the passing centuries), little attention has ever been paid to Odysseus’ wife, Penelope save to praise her for her constancy and her clever trick of unspinning at night all that she spun in the day. The occasional misogynist critic has dunned her, reading into her story his own gripes, but for the most part, she has remained a cypher.

Tiny once-upon-a-time bankrupt Edinburgh publishing house Canongate has tasked one hundred authors to provide one hundred short volumes about myth and retelling myths. The first three, published simultaneously, include popular religious author Karen Armstrong’s A Short History of Myth, Jeanette Winterson’s Weight : The Myth of Atlas and Heracles, and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad: The Myth of Penelope and Odysseus.

The book seeks to answer a few question that naturally arises if you consider for a moment the Odysseus household. Why did she wait? Why did she and her son Telemachus endure the suitors for so long? Why, when Odysseus did get home, did he kill Penelope’s twelve maids? And what kind of woman would marry a lying trickster?

To answer the last question first, either one incredibly smarter than him, the kind who can see through his lies and knows when to bring down the hammer and when to let him spin, or one like all the other people, a fool fooled. At first glance, there’s not much of a surprise in which way Atwood chooses to play things. Did you really think a feminist writer like Atwood would let Penelope have her say and then turn around and have this long-suffering wife be a blinking idjit?

Of course not. Nevertheless, despite how we’re supposed to believe feminists are humorless types, Atwood seems to be having a lot of fun here. Narrating from the afterworld, Penelope talks about life after death and how people used to bring them juicy bloody sacrifices, but now things have been upstaged by a showier place down the road, fiery pits and howling, a lot of special effects.

Starting with her childhood, there are amusing looks at Penelope’s pre-Odysseus life, such as trying to answer the question, how do you comfortably spend time outdoors with your father after his failed attempt to drown you by throwing you into the ocean? Along the way, Penelope dishes the dirt on such people like the stuck up, vain Helen, the original Mean Girl. “I suspect she flirted with her dog,” she tells us, painting her cousin as the vapid kind of big-chested bobblehead we’ve all known and shuddered at.

My only gripe here where Helen is concerned is practical and not literary. From a literary standpoint, we continue to pretend as though Helen were the real cause of the Trojan War. As though a growing, militant nation wouldn’t have any other reason to attack a rich and important port city that acted as a tollgate on one of the busiest trade routes in the ancient world other than a wayward wife. If only Saddam had kidnapped Laura Bush we’d have the same story in modern times.

Atwood’s Penelope, while she loves her husband, after a fashion (for, being an intelligent man he is neither as belligerent as his countrymen, nor so lacking in understanding of women as well as well as men), isn’t blind to his faults; she loves him in spite of them. Just as my wife might wait for me, so she waits for him. Likewise, the suitors who woo her by camping out at her house and devouring her livelihood don’t exactly paint a brighter picture for her future. Violent drunkards, disgusting lechers, and fortune-hunters, the batch runs from bad to worse.

However, the idea that there is some mystery as to why Odysseus would hang the twelve maids who reportedly slept with the suitors (even though being maids they had little choice most likely and “slept with” is a trifle more euphemistic than “raped”) doesn’t really stand up. While we must frame it to some degree in our modern mentality, what should a person of that time think of a woman, an employee, a member of his home, who was sleeping with his enemies? Having been away for years, Odysseus has no reason not to believe that these maids are in league with the suitors. Hanging them is pragmatic for the time and the mentality.

Atwood, despite such an easy answer, finds simple miscommunication behind it all. The twelve maids, she writes, were Penelope’s spies among the suitors. Yes, some of them were raped, and she tells us she grieved for them, yet oddly she never told the main maid, Odysseus’ nurse, Euriklea, the crone who becomes Telemachus’ maid in turn. Odysseus doesn’t have this bit of information and he kills the maids as traitors.

This is where Atwood’s story gets better and far more interesting. In the fashion of Greek myth, the book includes a Chorus — the twelve murdered maids. They themselves have their own version of events too, telling how Penelope had an affair with the nicest of her suitors, a secret the maids were in on. They say Penelope urged Odysseus to kill the maids to keep her secret.

This Chorus doesn’t let Penelope get away with a single trick either. The moment she veers toward self-pity they chime in to let her (and us) know that no matter how badly she thinks she had it, how poor her wedding feast or her regard in public, theirs was immeasurably lower. Slaves from their childhood, prey to the castle’s men, considered at times little more than rather intelligent animals, the maids were notoriously mistreated. Just as you begin to sympathize with Penelope, Atwood introduces these voices whose complaints ring even truer.

There is a nice puncturing of all of Odysseus’ adventures throughout the book. Instead of staying with a goddess, Odysseus merely slept with the madam of a high-priced whorehouse. Cyclops? No, just a bar brawl over a tab with a one-eyed bartender. Cannibals? No, just a fight that involved some ear biting, some bloody noses, a few slices to the belly with daggers. Men into swines? Well, there’s no magic there. Here Atwood misses a trick by not having the Chorus deliver the truth to the much more heroic versions. The whole story, when you really think about, comes off as a series of tall-tales, maybe told to a wife one comes home to and needs desperately an excuse for one’s tardiness.

The book’s ending explodes into multiple readings and revisions and re-revisions throughout, using curious devices like a trial to decide whether Odysseus was guilty of the unlawful deaths of the maids and whether or not Penelope was culpable. It culminates in the maids calling down the Furies on Odysseus, begging them to harry him wherever he may be, whether it be on the wine-dark sea or thesis page.

The maids add to this with an amusing anthropological dissection of the story with allusions to crop fertility, twelve-month representations in the maid(en)s, Odysseus’ homecoming as a patrilineal usurpation of previous matrilineal rule , his task of shooting a phallic arrow through twelve vaginal double blade ax-handles, before then turning the whole argument back on itself and suggesting that if you follow this train of thought, you neglect the very real possibility that twelve young women might really have been abused and killed.

That Atwood gives the final voice in the book to the maids leaves absolutely no doubt in her mind who she really backs in this fight. Though she may be seen somewhat as a bit genre-ish, a bit not as highbrow as many other authors, Atwood is one of the strongest feminist writers regularly spitting on her hands and taking up the non-polemical political novel. Her early work’s sometimes too overt didacticism has given away in these later years with a decidedly more playful spirit that toys with ideas in intriguing ways. The Penelopiad is a cornucopia stuffed into 192 short pages and the tight packed pressure gives the novel a fizzing bubbly quality not unlike champagne. It too goes to your head.

Reader Laural Merlington sounds like she’s having a lot of fun here, and that’s generally a good thing. The book’s Chorus of the twelve maids is the only part of the story that appears to be in verse, and it’s a clear answer to the question of how much dramatization and vocalization should a reader provide. In this case, less is definitely more. There are at times twelve Merlingtons speaking at once, then alternately she steps forward in character to deliver certain lines. All these voices have the hokey quality of digitized special effects, rising in pitch, multiplying, changing. While the Chorus has good lines to deliver, they are stepped over by this bizarro tactic.

No comments:

Post a Comment