Lady Chatterley’s Lover, by D. H. Lawrence, Read by Margaret Hilton, Recorded Books, LLC, 1988

Once cursed (or hailed) as the filthiest novel ever written, D. H. Lawrence’s last novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover is rather tepid by today’s standard. Oh, there are all the dirty words including the two biggies (“fuck” and “cunt”), but I really don’t actually believe that it is specific language that made the book so scandalous. Most likely the cause of the book’s bad reputation in its day was the rather open discussion of women enjoying sex, not procreative “this will give my husband an heir” sex, but the down and dirty, the riding a hot, throbbing cock inside you fucking.

And it’s not written condemning the woman for enjoying it either. Certainly she’s doing it as an infidelity; certainly she’s doing it with a sorta-kinda-not-really tacit approval of her husband; but Lawrence never tsk-tsks her for it. There is a kind of tradition as far back as Chaucer of wives indulging in affairs, but writhing underneath the sometimes comic, sometimes tragic tone of these stories, is a paternal moralism in which we are expected to condemn the wife and side with the husband. The flip side of this coin, errant husbands tomcatting about, never quite comes up for censure, unless the husband is particular flagrant about it or immensely promiscuous.

There were plenty of books available at the time and prior to it that were frankly sexual, books one bought privately or through mail order and which arrived in brown paper, books which if discovered could lead to prosecution for the owner and the printer, but nevertheless not the kind of books that caused societal upheaval. Just quiet trivial scandals providing little more than fodder for gossip. These previous pieces, particularly My Secret Life among them, generally published privately, were most commonly related as autobiographies of men and their sexual conquests. In the same goose and gander phenomenon as mentioned above, these men could get as busy with as many parlor maids, prostitutes, and other lower class women as their John Thomases could stuff, but upper class women were constrained (even as a taboo to break) from consorting with their social inferiors.

These two threads more than anything, I believe, were what fueled the rage against Lawrence’s novel. That the novel clearly had some literary merit, as testified by Lawrence’s vocation as man of letters, only made the offense even graver. Which is not to say that his career hadn’t been besmirched by charges of obscenity from the get-go. His third novel, Sons and Lovers, was declaimed as obscene too, a pattern which would follow with The Rainbow and Women in Love. Yet Chatterley is the one which created the greatest stir comparatively.

To be sure, none of those previous books contain the specific language on which formal charges were brought against Lawrence, but there is a decidedly curious thing to note upon reading the actual scenes from Chatterley. At nearly every instance of the use of the objectionable terms, they happen not in the midst of the act, but either preceding it or following it, and they are always used as dialogue terms, never as narrative ones. Chatterley and her lover, the gamekeeper, Oliver Mellors, have sex, then he lets loose with some comment such as: “That was what I wanted: a woman who WANTED me to fuck her.”

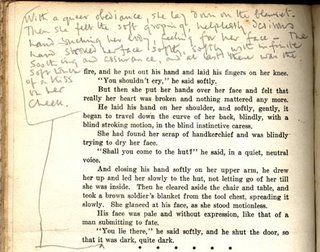

Further, the actual description of the act itself is almost always euphemistic, beautiful, but euphemistic nevertheless. Consider this description:

He too had bared the front part of his body and she felt his naked flesh against her as he came into her. For a moment he was still inside her, turgid there and quivering. Then as he began to move, in the sudden helpless orgasm, there awoke in her new strange thrills rippling inside her. Rippling, rippling, rippling, like a flapping overlapping of soft flames, soft as feathers, running to points of brilliance, exquisite, exquisite and melting her all molten inside. It was like bells rippling up and up to a culmination. She lay unconscious of the wild little cries she uttered at the last. But it was over too soon, too soon, and she could no longer force her own conclusion with her own activity. [emphasis mine]

He is always baring “the front of himself” and he is forever grabbing her and doing things like “short and sharp, he took her, short and sharp and finished, like an animal.” Things happen quickly and rapturously and vaguely, then afterwards, it’s all cunts and cocks and arses. But only to talk about and never in any real explicit fashion. Oddly enough, it is the same technique employed by modern hacks like Eric Jerome Dickey. Authors present themselves as hip and sexually open and brave and full of all the dirty words, then they flinch at the actual getting down.

This is both a kind of cowardice and a kind of literary self-preservation. One can approach the sacred mystery in all its funky, nasty thrusting and liquescence and descend into a kind of anatomical role call of parts and activities, or you can stop short, avert your gaze and focus on the transcendent sensations. The former group never truly escapes the tag of “pornographer” while the latter some day might get the call up to the acceptable literary big leagues. It has oft been a dream of mine to teach a college English Literature class focusing on the naughty boys and girls of letters whose names were slurred over in their day.

At any rate, Lawrence is both less and more than his reputation. Less in the sense that time marches ever over one’s laurels, trampling them in the mud, moving the acceptable goalposts until the hard fought inches you struggled for all your life turn up on every cable channel after dark for lurid, prurient interest. Less in the sense that whatever his reputation, his books are humorless, frequently racist, sexist, and all-in-all still stiff upper lip Britishly puritanical. Times change and all your naughty bits become acceptable and all your acceptable bits become naughty.

And then again, Lawrence is more than his reputation because he did move those goalposts. Because he did dare call a spade a spade and fucking fucking. And more again because it doesn’t just come down to scrawling four letter words no matter where they turn up in the manuscript, but because it expands our minds as to what corners of real life literature can shine a light on. Because he made the natural seem natural, and not shameful and dark and some kind of nasty thing, but ordinary and everyday and pleasant. Because even divorced from reproductive acts, Lawrence’s prose often soars on a kind of all-encompassing metaphor, life reduced and made simple, yet made translucent so all the shimmering glow of existence could shudder forth, breaking out of contrived molds and literary constraints. An enemy of the alienating effects of the modernistic, mechanistic mold society was making for itself, Lawrence posited the body in an age where it seemed less necessary and in a place that chose to pretend it didn’t exist.

For this, at least for this, he had the courage, and for this at least, we owe him remembrance.

No comments:

Post a Comment