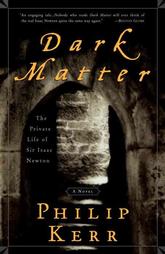

Dark Matter, by Philip Kerr, Read by John Lee, Books on Tape, Inc., 2002

It’s in moments when I get most discouraged about the historical mystery/thriller that someone comes along and cleans my clock but good. I’d been interested in Philip Kerr’s Dark Matter for as long as I’ve been seeing it on the shelf at the library, but my local branch only ever had the abridged version, which is almost as good as having nothing in my opinion. One day it occurred to me that the library might actually stock both the abridged and the non-abridged — and what do you know? — they did.

Now as far as I recall, historical novels used to be about the little people from momentous times past. Certainly noted notables used to make appearances across the stage, the Queen passing in her carriage or Cortez in regal parade, but for the most part the action was focussed on the plebeians, characters one assumes most readers would relate to better.

That has changed of late, and more and more we are seeing historical novels in which it is the plebeian who makes a brief appearance, setting up the tea things, driving a hackney coach, being despoiled upon an alter, or what have you, while the giants of the age strut and pose center stage. What’s more, there seems to be a fashion for putting said notable in unfamiliar postures, thus a West Point cadet Edgar Allan Poe or Jane Austen as detective or what have you.

Dark Matter, Kerr’s 2002 novel starring Sir Isaac Newton and told by his real life assistant Christopher Ellis, does just that. What makes his book superior out the gate in comparison to others is that surprisingly little has to be invented. Longfellow & Company’s chasing down of a murderer in The Dante Club, while entertaining, comports with few facts of their lives. That our detective Newton, who served as the Warden of the Royal Mint, should appear here hot on the trail investigating both counterfeiting and murders related to it requires absolutely no invention whatsoever. Indeed, he was a tireless, incorruptible, methodical investigator, so dedicated to the work that he died still employed by the mint, though having risen to the position of Master of the Mint.

When we first meet Sir Isaac as seen through the eyes of his assistant Ellis, Newton provides him with a Holmesian observation of his life and his recent activities such as judging he drank red wine heavily last night due to some stains on his shirt cuffs and the odor of juniper berry ale around him (often drank as a hangover cure at the time). He also notes Ellis’ skill in the fighting arts:

“Come, sir,” insisted Newton. “Did you not pink a man with your rapier?”

“Yes sir,” I stammered, angry with my brother for having apprised him of this awkward fact. For who else could have told him?

“Excellent.” Newton knocked the table once as if keeping score. “And a keen shot, I see.” Perceiving my puzzlement, he added, “Is that not a gunpowder-spot on your right hand?”

“Yes sir. And you’re right. I shoot both carbine and pistol, tolerably well.”

“But you are better with the pistol, I’ll warrant.”

“Did my brother tell you that, too?”

“No, Mister Ellis. Your own hand told me. A carbine would have left its mark on hand and face. But a pistol only upon the back of your hand, which did lead me to suppose that you have used a pistol with greater frequency.”

The duo, in the mode of that famous prototype, set about their investigation into who is making false coin in such quantity and quality that it might undermine the project of the Great Recoinage (King William’s codification of coins by weight, size, and purity), tank the British economy, and destroy the hopes of defeating long-time enemy France. When a spy working for them ends up dead inside the royal lion cage, his body marked with arcane alchemical symbols, their investigation expands. As more bodies pile up, the conspiracy turns out to be greater than originally imagined, adding up to a planned genocide of Catholics and an overthrow of the monarchy itself.

In the course of the novel, we are treated to a number of historical curiosities: alchemy, how kidney or bladder stones could lead to death, the history of London Tower, the Knights Templar mythology, Huguenots, and intrigues between the French and the English, Catholics and Protestant. We will also meet rascally Presbyterian intriguer Daniel DeFoe; Newton’s friend and Royal Society cohort, Samuel Pepys; and the vile anti-Catholic bigot, perjurer, and seditionist, Titus Oates.

Kerr keeps all of this going with good humor and occasional lectures to Ellis from Newton upon the motion of the heavenly spheres and other delectable simplifications of themes from the Principia. His Newton, as reported elsewhere, has a caustic wit, describing one man: “He is a drunken borachio and so arrogant I do believe he must wipe his arse with gilt paper.” The portrait is fond even if he is throughout represented as a rather humorless prig, a personality not at all at odds with many biographies of the man. Ellis himself is a treat, a brawler who would improve his mind and who loses his bawdy romance with Newton’s niece through his atheistic heresies. The voice of Ellis has a sedate, perfect period ring, a touch of the vulgarly earthy amidst syntactical complexity one rarely comes across in print anymore:

We made our way to Newgate, where, my master, being recognised from one of the upper storey windows, and much hated among the prisoners for his great diligence, was obliged to dodge a bole of shit that was thrown at him, and with such adroitness that I did perceive how, for all his fifty-four years, he was a most athletic man when the occasion demanded. Entering at the gate, he made light of the ordure bole, saying that it was as well that it had been an apple that fell on his head and not a turd, otherwise he should never have thought of his theory of universal gravitation, for he would have had nothing in his head but shit.

The resolution of all of Newton and Ellis’ inquiries, leading as it does higher and higher within British aristocracy and government, has a nicely unsettled and unresolved aspect to it, even if the pair do solve the crime and uncover an even greater one. Kerr’s tale, told with vitality, wit, and an attentiveness to period detail, has a vividness and a depth missing from a great many other historical novels wherein the authors merely pile on accretia of facts to what amounts to anachronistic characters and attitudes. Kerr’s characters feel real, feel like human beings. The book reads as if it truly were the document it purports to be. That’s how one writes an historical novel, thriller or no; you write it like it was lived. Come to think of it, that’s how you write a great novel.

Reader John Lee may be the British equivalent to America’s George Guidall. He is neither flashy nor mind-blowing; one never listens to a book by either man and comes away going wow! what a reading, yet one is never dissatisfied either. Solid, listenable, dependable work that is so flawless as to be near impossible to critique. The men could read me the phone book and I’d be in heaven still.

No comments:

Post a Comment