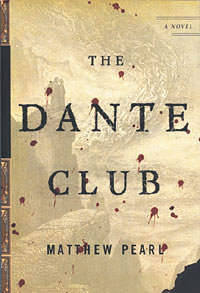

The Dante Club, by Matthew Pearl, Read by John Siedman, BBC Audiobooks America, 2003

As regular readers in this space know, I have a weakness for historical mystery/thrillers, especially ones that illuminate periods of time or personages with whom I’m only fuzzily acquainted. I once told a friend, when we were both in our thirties, that I’d only recently discovered the fact that Longfellow was an American. He laughed at first, thinking I was joking, then his eyes rather bulged. Having never read any of the man’s poetry, I just lumped him in with the Lake poets, expecting that I’d get around to reading him in one of my periodic poetry binges.

That day of familiarity was hastened by Matthew Pearl’s fascinating novel, The Dante Club. Part history of the difficulties experienced by Longfellow and his colleagues in not only translating but also publishing the first English translation of Dante’s Commedia and part gruesome murder mystery, Pearl’s novel teaches while it entertains and makes the lives of poets seem filled with intrigue and passion.

Pearl wins my admiration from the beginning for writing in the “lost manuscript” tradition, perhaps my favorite sub-sub-genre of historical mystery, the story revealed only once the dusty old manuscript is uncovered. Secret histories have a fascination all their own, and Pearl’s gets to play, like his novel, with the real and the imagined. The history of Longfellow’s translation is a widely unknown story, while the hidden murder thriller is the fictional secret tucked away in the past. The opening pages frame this as a story told by an unnamed academic seeking two lost privately printed copies of Longfellow’s translation of The Inferno who found something else entirely.

The story itself proper begins with a detective waiting in a New England Brahmin’s Boston home, expecting the return of the wife in order to inform her of the details of her husband Chief Justice Healy’s death. It is an arresting beginning, strangely told and riveting. There is something off and mysterious about Healy’s death, his body found naked and maggot covered by the river’s edge not far from his home. There will be more murders as the book goes on, each more gruesome than the last, all of them strange and all of them related to the suffering of the damned in Dante’s poem.

We next find ourselves in the Cambridge offices of J.T. Fields, the publisher of our three poet heroes, Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. He and his firm are on the verge of publishing Longfellow’s Divine Comedy, though his efforts aren’t without their difficulties. The poet seems to be have slowed down considerably and powerful interests in the Harvard Corporation are against this introduction of savage Catholic ideas. It could, they believe, incite the influx of new immigrants from Ireland.

Through this office we meet almost all the main characters save the most prominent of the poets. Oliver Wendell Holmes, worried about being slighted in payment for his most recent submission to The Atlantic, asthmatic and self-conscious enough about his slight stature to wear “elevated boots.” James Russell Lowell, brash and confident, a former student of Longfellow’s Dante class and now a professor himself at Harvard. Cameo celebrities also pass through Field’s door such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and later Robert Todd Lincoln and William James.

The relationship among the friends and Dante Club members is part of the charm of Pearl’s novel, such as the competitive and often fractious relationship between Holmes and Lowell, partly based on the former’s support for the Runaway Slave Act (repatriating to the south any captured slaves). Still simmering abolitionist arguments pervade the atmosphere of the novel which takes place in the year 1865, just months after the end of the Civil War and the assassination of Lincoln. Both men also look upon Longfellow as something of a father figure.

In telling of how Longfellow came to Dante, how he was seized by a mournful writer’s block following the death of his wife (her dress catching on fire and he wrapping her in a rug, but too late), Pearl (and Lowell) conclude that the man could only find solace in the art of translating. It’s a gentle, beautiful passage, and Siedman reads with an appropriate dying fall to his voice:

Lowell believed he understood quite well the reason Longfellow had written so little original poetry over the last few years in his retreat into Dante. If it were his own words Longfellow was writing, the temptation to write her name would be too strong and then she would merely be a word, no longer alive.

Into this literary, intellectual world comes the murders. While I expected the possibility of grave disappointment upon reading yet another serial killer novel (especially one featuring yet another diabolically clever murderer whose crimes mirror some artistic source), Pearl manages to make not only the carnage intricate but his villain’s interior world as well. As much a victim of his time as so many others, Pearl takes a damaged mind and shows it working efficiently on its own bent logic.

But the family dynamic surrounding Longfellow is where the book’s real interest and spirit lies. The killings are almost a distraction from Holmes’ wounded pride, Lowell’s blustering temper, Longfellow’s tender affections for his daughters and his aching widower’s heart. Pearl grounds these complications and these shifting levels of emotion among the group with well crafted characters whose reactions are predicated on their real life counterparts.

So much of the novel is merely history, that when the group begins investigating the crimes, finding itself the sole possessors of the knowledge that they are related to Dante, it never seems forced or overly comical that three middle aged poets should turn their attention to this business. Each is in one degree or another active in causes of social justice or simply desirous of protecting Dante from slanderous connections.

The Dante Club also works wonderfully at demonstrating how one’s own beliefs can blind even the most intelligent people. The Club labor dangerously for most of the novel under a fundamental misconception, so much so that Pearl misguides the reader along that same path. Intertwined we fine the historical backdrop of the day such as anti-Catholic fervor against the rising number of Irish immigrants, the status and society of black Americans in the post-Civil War Boston, and the political machinations in nineteenth century Harvard. The first and last directly relate to Longfellow’s translation, while the second aspect finds its expression in Pearl’s truly fine creation of the fictional Nicholas Rey, Boston’s first black police officer. Rey allows us access to worlds the poets can’t penetrate and provides rigorous detective work to their artistic speculation.

As the book moves towards its conclusion, Pearl never loses sight of the literary/philosophical nature of the novel and doesn’t fall into easy chase conventions. It’s a rather pleasant feature to have an adventuresome poet like Lowell who delivers a “lusty tackle” to a young man and aims his rifle in ambuscade of a slimy Pinkerton detective. Yet at the same time, in a nod to Arthur Conan Doyle, who many believe partly based his detective on Oliver Wendell Holmes, it is a fine thing for the timorous scholar to find his own courage in his own moment of truth.

The book’s final chapters are written in such a breathless style, the thriller element of the plot taking over for the home stretch, that I grew agitated listening. I wished to have a print copy in hand so as to race along to the conclusion even faster than the audio narrative would allow. Pearl demonstrated at this crucial juncture an expert sense of pacing and interior rhythm, knowing just when to let the poetical speculation fall by the wayside for pulse-pounding captivation to take over.

While I’ve long since finished Pearl’s novel, I have been since then savoring the particular beauty of Longfellow’s translation. It is the final box into which this lost manuscript novel fits, the story within the story that itself actually contains the story. Many more translations have followed, some with more felicity to Dante’s Tuscan Italian and some with a beauty all their own. While Longfellow’s version may be long on archaic phrasings and heavy with the Romanticism of his day, it retains a special place in American letters and it’s as good a place as any for meeting a poet or two.

Reader John Siedman makes a game attempt at delivering up characterizing accents though he seems to have made Lowell resemble Longfellow and Holmes resemble minor partner George Washington Green in pitch and inflection. Smaller, poor characters with less lofty accents come off better and more distinct. The narrative itself is pleasant, lively, and Siedman never loses the thread of Pearl’s sometimes clause nested sentences.

No comments:

Post a Comment