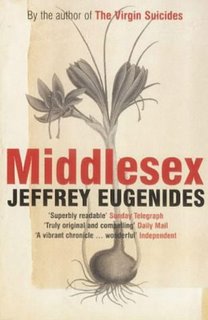

Middlesex, by Jeffrey Eugenides, Read by Kristoffer Tabori, BBC Audiobooks America, 2002

When people foolishly talk about the death of the novel, it’s clear they’ve missed reading Jeffrey Eugenides’ fantastical, amazing, and beautiful Middlesex, a sprawling family history that is a national history as well as one of the finest novels of transformation, mythology, and sexual relationships written in many a year. Quite frankly, during and after reading it, I floated around with a big ass grin on my face, simply marveling that a species regularly capable of such crap can scale such heights of pure pleasure.

Simply put, it is the kind of novel that can make you have faith in life all over again.

Which is kind of funny when you read the book and become acquainted with just how much suffering, misery, and torment the characters endure, though always with a joke somewhere. A laugh wrung from the bottom of one’s soul is a laugh still. Nietzsche once wrote that the human animal was the only one who laughed — and laughed because he needed to.

Meet Calliope Stephanides, or rather, our narrator Cal Stephanides. And if that seems somewhat confusing, then I’ll let the novel’s opening sentence clarify things for you. “I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974.”

Part coming of age story, part family saga, Middlesex can also be seen as the life story of several generations of 5-alpha-reductase deficiency. This genetic mutation prevents the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the necessary hormone in the expression of male genitalia in utero. Thus, a person is born with XY chromosones as well as testicles and usually labia, a vagina, and a small penis in place of a clitoris.

Which is why our hero, born a girl named Calliope, grows up to be a man named Cal, working for the American Embassy in Germany and telling us the story of his family.

Because in a story about genetic mutation, we will have to know of the various genetic combinations that led us to this point. And so the novel flashes us back to just before the 1922 war between Greece and Turkey, to the small village where live Lefty and his sister Desdemona, two of the only young people left in their dwindling hamlet, who tend to the family business of silkworm farming. Through the chaos of their lives as the Turks invade and eventually burn the city of Smyrna to the ground, Lefty and Desdemona fall in love and set sail for America.

Indulging in a complicated ritual of “meeting” and courtship on board the ship sailing to the new world, the siblings consummate the marriage awkwardly yet tenderly. In America, they move in with their cousin Sourmelina, and eventually Desdemona gives birth to Milton, then later a daughter. Milton grows up to marry his second cousin, Tessie, Lina’s daughter who now lives in the house behind the Stephanides in this close knit Greek community near Detroit. Milt and Tessie give birth first to a normal boy, who is only known in the novel by the name Chapter Eleven (he later bankrupts the family business), and a girl, Calliope.

While we have an incestuous patrimony, the inbreeding and small, closed culture of Greek families come out in ways such as this genealogy, as delivered to Calliope by her mother:

That’s your cousin Melea, she’s uncle Mike’s sister Lucille’s brother-in-law Staphis’ daughter. You know Staphis, the mailman who’s not too swift. But Melea’s his third child after his boys, Mike and Johnny. You should know her. Melea! She’s your cousin-in-law by marriage.

If there were a community better suited literarily to the vagaries of intersexed peoples, I can’t think of one more so than the Greeks. And so Eugenides’ novel reads like an epic or myth and touches on various elements of Homer (such as when late in the novel Cal runs away to California where he ends up in an aquatic peep show with a woman in a mermaid costume, an odyssey of a kind). At every point where Eugenides could take a situation that unfolds perfectly naturally and inject it with mythic significance, he does so, the effort never seeming forced or too contrived for effect.

A good example is the framing the author provides for the night of the dual conception of his mother and father. Cal documents this, and Eugenides displays his interest with an astounding beauty and near allegorical significance. Having just returned from a night out to see, of all things, a play called The Minotaur, the two couples are gazed down upon:

Freeze the action. A momentous night this, for all involved, including me. I want to record the positions. Lefty: dorsal, Lina: couchant, and the circumstances: night’s amnesty. And the direct cause: a play about a hybrid monster. Parents are supposed to pass down physical traits to their children, but it’s my belief that all sorts of other things get passed down too: motifs, scenarios, even fates.

The language, never overtly ornate so as to attract attention to itself, nevertheless allows Cal’s story to move such breathtaking obviousnesses like the Minotaur on to center stage as naturally as any other character such as Father Mike, the docile-seeming Greek Orthodox priest, or Jimmy, Lina’s teetotalling bootlegger husband.

And much like a more serious version of My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Eugenides provides us with a kind of anthropological survey of Greek traditions such as leaving a man at the home of the deceased for the two hours of the funeral so the spirit can’t get back into the house, the kinds of food served afterwards, and the forty day mourning period, as well as the crown ceremonies during weddings, the sex segregation in the homes, the differing terms of endearment for your beloved young wife and for her after the birth of the children, among other things.

And you just shake your head at nearly every turn, where Eugenides finds a way to fiddle with the usual story line and provide wickedly ironic smiles. As the 1970s penchant for busing in the public schools hits Detroit, Milt decides to send Cal to an all-girl’s school. An as yet undeveloped intersex character in an all girl’s school! It’s simple, believable, and wonderful. As an author, Eugenides is assured enough even to go for broad gestures such as the theatrical production at Cal’s girls school of Antigone and the casting our narrator as — who else?— Tiresias, who was born female and became a man.

It is here then that Calliope will fall in love, will partly consummate it with a character referred to only as The Obscure Object, will discover sex with a male, and will have an accident that will wind her up in the hospital.

The book’s fourth part follows Calliope as her hermaphroditism is discovered by a doctor and she undergoes tests at a special clinic. This portion of the novel takes a lovely turn at a moment where Calliope consults a dictionary while her parents go to the doctors for the final summary by the physician. Researching terms she gleaned from her medical file, Calliope comes across various “see hypo” this and “see hypo” that, including a chain of verbal causality leading to “hermaphrodite” and finally, sadly, “monster.” At this point, the book’s narration shifts from first person to limited third, the “I” of this scene slicing itself off entirely, the girl Cal was severed from who he has become. It lasts briefly, it passes in a few pages, but it is a masterful stroke of prose. In one shift, the narrator’s own disconnection from his/her own life expands and becomes completely overt, accessible to us as readers.

The moment of final transformation comes when Cal enters a barber shop for a haircut. Looking into the mirror, our narrator sees the girl Calliope looking out for the last time and then the hair grown over the years is buzzed from his scalp. From here, Cal hitchhikes to California, of course running into chickenhawks and other such types. There, in San Francisco, naturally, when his money runs Cal falls in out with Bob Presto, former DJ and now announcer for an unusual peep show, trannies and pre-ops, supposed mermaids, and, of course, Hermaphroditus, greek goddess.

There are wonderful observations when Cal comes back from California as a man, such as Cal’s mom Tessie still griping to her new son as though she might to a daughter, complaining about men and the two of them getting their hair done together. There are scenes such as when Chapter Eleven fetches Cal’s suitcase out of the car trunk, then pauses and tosses it to him. You can carry this yourself, bro, he tells the person who used to be his sister.

Eugenides rightfully won the Pulitzer Prize for this beautiful novel filled with enchanting sentiment, and he makes you love even the characters who annoy you; even the jerks are treated as human beings. He’s the kind of writer who, when he gives you Milt’s death scene, turns it briefly to a flight of fancy, then draws a little almost tearful laugh out of you with Milt’s final summation of himself: “Knucklehead.”

Amazing moments happen everywhere. The early introduction to the Greek tradition of a man staying home during a funeral to keep out the ghost is revisited at the end as Cal, now publicly and obviously physically male and wishing to avoid complicated discussions at his father’s funeral, is the one who takes this task, newly minted as a man. Even the book’s final sentences, the fulfillment of a miniscule promise made much earlier, is a commonplace given the weight of symmetrical beauty.

Reading this book, you will find yourself nodding again and again. Yes, you will be driven along by the narration, yes, everything will fit together perfectly, naturally, yes, you will cry and you will laugh and you will know beauty.

BBC Audiobooks America does a wonderful job of finding stage actors with a lovely way of fleshing out novels’ characters. Here Kristoffer Tabori, with his high, at times almost girlish voice, takes on all the various types, accents from the Old Country, Brooklyn, smoky voiced pre-op trannies, Detroit ghetto soapbox ranters and Muslim convert women, males, females, and all the rest. He delivers like a champ; he is our Tiresias and we couldn’t ask for a better one.

No comments:

Post a Comment