The Stranger, by Albert Camus, Translated by Stuart Gilbert, Vintage, 1954.

Prior to this, I probably read Camus’ landmark novel, The Stranger, three times in my life. Once in high school (with a teacher who pronounced the author’s name AlberT Caymuss), and twice in college. I hadn’t read it in about ten years or so and was in the mood for something short, but something familiar, too. Because of its brevity, the novel has remained in my memory very distinctly.

What I kept waiting for, though, was that moment when my older self would think, "Ahhh, well, that was an element of the story I had overlooked." Quite possibly Camus' intention in aping Hemingway's style was so that he could deliver the story without a great deal of “what happened” ambiguity in order to focus on the conflicted, confused state of the narrator's mind. What is most easily recalled from this novel is the first half leading up to the shooting, the action part of the story. The imagery there stays with one – the flashing of the knife on the beach, the mangy dog whose owner beats him and weeps for his loss, the narrator’s sexual relations with Marie, and the people associated with the funeral of Meursault’s mother. There is a kind of narcotized sensuality throughout the beginning that is almost absent from the second half where the book makes a decided interior shift.

Having now finished the novel for the fourth time (and as part of a sudden yen for existentialist writers' fiction) what strikes me more now is just that second half. In prison, Meursault reflects on his sentence, the idea of justice and of what death really means. There is a great deal of similarity of thought and idea with Sartre’s earlier short story “The Wall,” in which a prisoner condemned to death in the Spanish Civil War has time to reflect on his impending death.

In fact, the two narratives offer up a great deal of overlap. In both instances, there is a fantastical use of absurdity, one of existentialism’s lynchpins, there are narrators who try to face as bravely as possible their coming negation, and there is a rejection of god and religious cant. Where Sartre’s story uses an O. Henry style twist to deliver the absurdity of life, weakening his depiction of its pervasive nature, Camus makes the motivelessness of Meursault’s crime as the philosophical starting point. Sartre’s story seems almost to suggest that life is absurd so it perhaps may not matter what course of action you take whereas in Camus, the absurdity of life forces you into action.

Where the two stories differ in direction is that although Meursault at one point dreams of escape from his situation, he nonetheless finally accepts it. This is in keeping with Camus’ beliefs that one defines oneself through one’s actions – including keeping up a ridiculous pretense when it doesn’t suit. Death with dignity is what finally Meursault is able to accept, a kind of “gentle indifference” to the world and its machinations. He has worked his way, thoughtfully, to a kind of truth about himself, society, and his place in that society. In Sartre’s story, the narrator Pablo Ibbieta, resists all the way up to the end of the story, his last act of defiance masquerading as compliance. While he experiences the torments of realization that his existence is about to end and mentally works his way through the meaning of this, he chooses not to go gently, not to be indifferent to the world about him.

An essential text for disaffected, intelligent high schoolers and college kids, The Stranger nonetheless remains compelling reading even after one has passed through life’s more angsty stages. Camus’ prose is leanly poetic (though it falls short of the stylistic mastery of Hemingway) and his novel’s conclusions are worth mulling over. While the novel is hardly close to death, the philosophical novel remains a bit more moribund. Perhaps it was always thus, but in around 150 pages, Camus demonstrates with ease how a pistol doesn’t have to be the end of the argument.

5 comments:

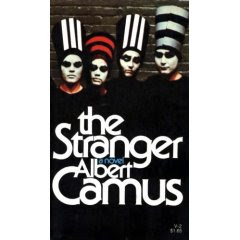

And, yes, I chose this ridiculous cover because that's the one I have. WTF is up with this? I've been wondering since freakin high school.

I know the old "you can't judge a book by its cover", but I find bad covers very distracting. I can't help but let it set the underlying tone for the whole book.

Is the cover from the mid-80's?

My high school French teacher wanted me to read this in its original French after we read Sartre 's Les Jeux Sont Fait. I never got around to it, and now that my French is all but a distant memory, I'm not sure I want to read it. Silly, I know, but that's just the way I am.

If you've never read it, it's well worth your time, which would run somewhere in the two hour range. Tops.

That's the copy I have. Camus, Camus, you make me blue!

I've only read it once. My adolescent angst is still too close to the surface for me to read it without repercussions.

Post a Comment